There are two main rules to follow when setting up a religion; first, never make a claim for the end of the world and second, never claim immortality for your leader. While the Panacea Society did not make the first mistake, they fell full prey to the second. Not only did they claim immortality of their leader, Octavia but also for each of them. Now the religion is no more but they had a good run of it, over ninety years of faith carried out in the Holy Town of Bedford.

Last year I visited the Holy Town, to The Campus, home of the Panacea Society. I even had tea and lemon drizzle cake in the garden, believed by the Society to be the Garden of Eden itself. It was a beautiful July day and as I sat there with my refreshment, watching a blackbird singing on a bush, I could see how the Panaceans felt as they did.

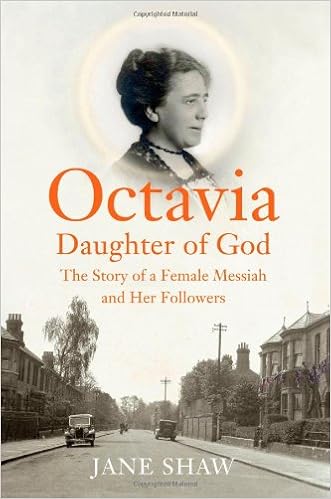

It was in Bedford that I bought a copy of ‘Octavia: Daughter of God’ by Ruth Hall at a price I began to think may have been an accident. The book was written in 2011, when there were still a couple of Panaceans left alive. She was given full access to the archives and free rein with all the secrets and hidden doctrines. This is partly due to the fact that the book and the project that the book was part of was funded by the Panacean Society after urging from the charity commission to liquidate their wealth and do more with it. This may mean that the book is too kind to the Octavia and the society but I don’t think this became an issue.

First we learnt about Octavia herself. What sort of person becomes ‘the daughter of God’? What sort of people confirm her in this notion? How does a religious community spontaneously come together in the first place? These were all fascinating questions and were well explored.

Octavia, originally Mabel Andrews, was a London-born member of a family with literary connections. She was intelligent and a voracious reader but did not receive an education more extensive then any other girl in her time or place. She married Arthur Barltrop, a curate whose career was hampered by ill-health. A keen reader of his theological library and a vigorous worker for charities, she took an interest in the church and religious matters. When he died, she lived in a respectable house in Bedford with her children.

Always prone to nerves, she was (at least once) committed to a mental hospital, where she was dismayed to be treated like a crazy person. There she discussed religion as well as the many other new spiritual categories like spiritualism and theosophy. Having read works on Joanna Southcott, she wrote letters to bishops to get her mystical box of prophecy opened.

Coming back home, she carried on her interest in Southcott, taking part in letters and later meetings with other Southcottians. She was linked into a whole network of people who felt that the Anglican church was in some ways dead, cutting itself off from new ideas that could inject new life into it. Many of these people were women, cut off from careers in the church, they began to cohere into a religious community of their own where women did all the main jobs. Although many of these early members were suffragists and even suffragettes (one had gone on hunger strike in Holloway Prison), Mabel Barltrop herself felt that women were essentially different from men and it was this difference that made them vital to reviving true religion.

Many of these people were involved in currently popular practices like automatic writing and Mabel became one of them. The community began to regard themselves as the real church, connecting themselves with Joanna Southcott and the prophets that came after her, a line called ‘The Visitation’. A recently deceased member, Helen Shepstone, was declared the sixth prophet of this lineage, then the idea grew that Mabel was the eighth. As a result she took the name Octavia. Soon after, it was revealed to a member that Octavia was not only the eighth prophet but Schiloh, the spiritual child of Joanna Southcott and the direct daughter of God. In the letter where Octavia recognised the call and took the responsibility, she also thanked a friend for knitting her a lovely pair of bed socks - so the spiritual and the mundane mixed for this group.

With the belief that God’s daughter was among them, the new ‘Community of the Holy Ghost’ formed the notion of a four-square trinity with Father, Son, Holy Ghost and Daughter, this developed into the notion that the Holy Ghost was also the voice of the Divine Mother, creating something of a nuclear family. Octavia’s own mental sufferings became a subject for belief, so Jesus had suffered bodily for the soul of humanity, so Octavia had to suffer mentally to save the humanity’s bodies - for if a follower managed to live the tenants of the new faith, they would be bodily immortal. When 144,000 people had achieved this, then there was a foothold on Earth for Jesus to return and establish the New Jerusalem in Bedford. The town was initially favoured for it’s good shops and new Selfridge’s department store, but as beliefs grew, the notion that Bedford was a holy place and the garden of ‘The Campus’, the houses around Albany Road the members bought up, was the Garden of Eden. Octavia believed that if she walked 77 paces away from the centre of it then the Devil would kill her, so was essentially imprisoned into her base of operations.

The key to bodily immortality was a process known as ‘Overcoming’. The idea was to become ‘comfortable to live with’, to overcome all the irritations and annoyances of normal life and become something better. One of the ways to do this was to write a large, permanent confession, not only because confession was regarded as good for the soul but because the Panaceans believed that each confession was an accusation with which to imprison Satan. On the more mundane level, there were strictures to not eat toast noisily, to put plenty of cherries in a cherry cake and a two page instruction manual of how to make tea. It was important to do these small activities perfectly to promote all around perfection.

As the society ‘regarded as true, anything that was interesting and meaningful,’ coincidences often helped form their beliefs. One day Octavia’s medication jumped out of her hand so she prayed on water and drank it. Drinking this blessed water was spread over the community until they developed a system where Octavia breathed over rolls and rolls of cloth which were cut up and put in water. This turned into a worldwide healing ministry, with thousands of people writing in for the cloth (and reporting their progress) up until the 1990s. This water was the ‘panacea’ that the society later took its name from and was one of its main activities other than putting up posters in London demanding Bishops open Southcott’s Box.

Where the early society was a community of believers centred around a charismatic leader, the functions in the community became stricter. When an American seeker of knowledge entered the community and started preaching that gay sex was spiritually neutral in a way straight sex wasn’t, he was ‘tried’ and expelled under the ordinances of the ‘Voice of the Divine Mother’. Emily Goodwin has originally been the nurse to Octavia’s Aunt Fanny but quickly became the enforcement arm of the Panaceans. Although Octavia was regarded as the Holy Daughter herself and Emily was only the conduit of the voice of the Divine Mother, anything said in that voice was regarded as absolute.

In its prime, the community had been a thriving place with garden parties that were regarded as rehearsals for Heaven on Earth but as everyone grew older and many died it became a place for ‘old people, cripples and the feeble-minded.’ If the book is accurate, the joy of the thing withered as it became tighter.

You can imagine the surprise when Octavia died in 1934. The members stuffed her bed with hot-water bottles and waited, just as Southcott’s followers had done, and much with the same effect. Octavia started to rot and leak fluid from her nose. She was buried under a quiet and unassuming gravestone.

The Society kept going though, buying a house for Jesus’ return, expanding the healing squares and taking adverts in papers about the Box. Even as this book was written, there were still two believers who kept things ticking over. They were in the process of doing up the building kitted out for the Bishops and creating a museum. By the time the museum was opened, the followers had died at the society turned into a museum trust. It’s a museum well worth visiting and this is a book well worth reading - there was loads of interesting stuff I missed out.

Incidentally, as I chatted with the man at the front desk, he told me that although the Panacea Society did not exist, there were still dedicated Southcottians and some of them in Bedford.

No comments:

Post a Comment