Shark Alley by Stephen Carver purports to be the missing papers of forgotten writer, Jack Vincent. In his heyday one of the set of writers that included Dickens, Thackery and William Harrison Ainsworth, but now writing penny-a-line for newspapers. He has been sent on the troopship, HMS Birkenhead, which suffered a real tragedy when it sank in shark-infested waters. The book cuts between flashbacks to his life leading up to boarding the ship, and his experiences of the ship and with the tragedy

I love how Shark Alley commits to its bit. The blending of real and fictional characters and incidents is balanced really well and the book even includes endnotes by ‘editor’ Carver that explain how and why Vincent has been lost to history. There’s also an endnote, where Carver explains how he finds the papers, stealing them from a hiding place behind a copies of ancient Daily Mails in a dead hoarder’s house.

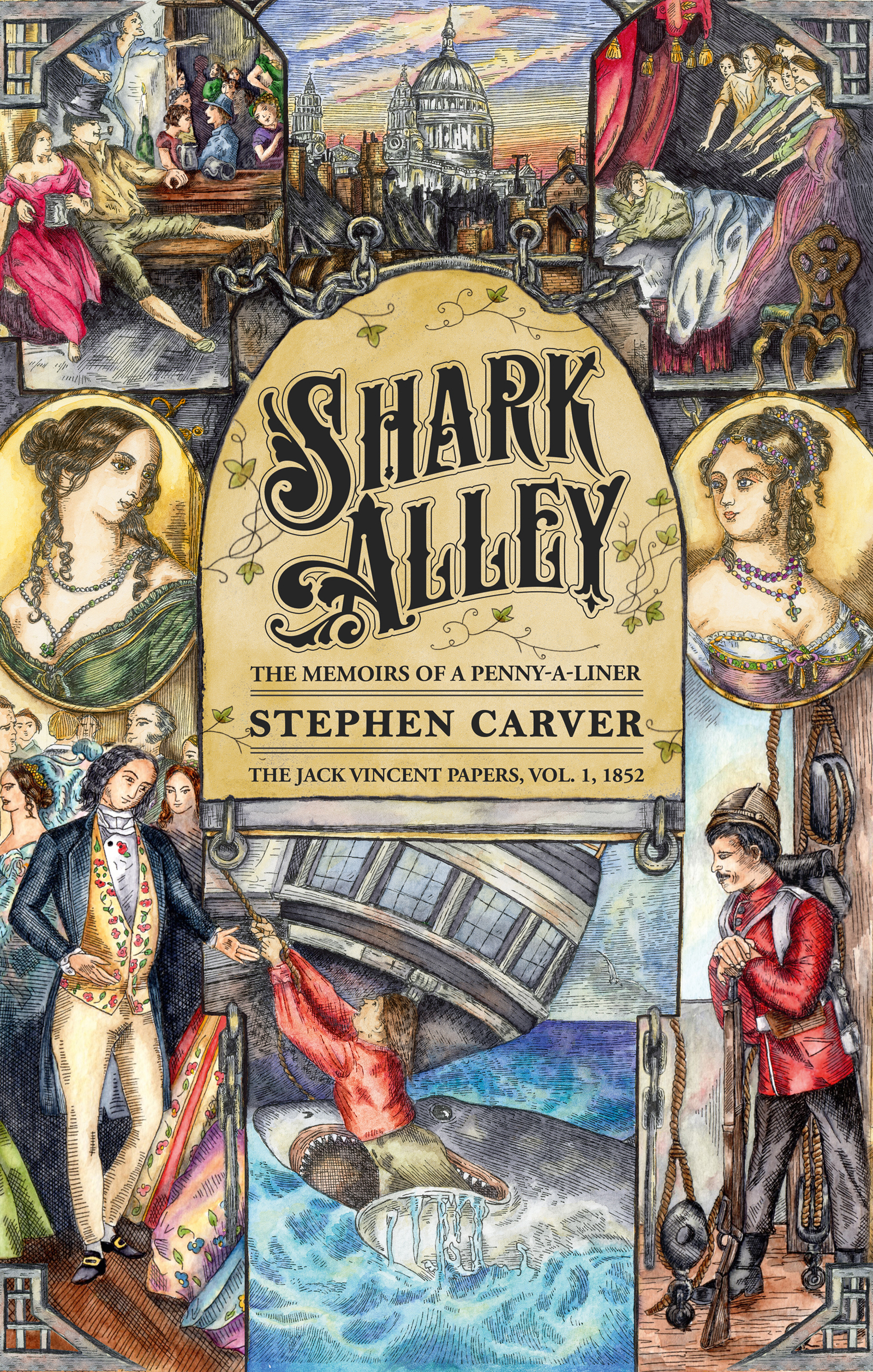

The cover is also gorgeous with a real ‘boy’s own’ style. Originally the book was written in instalments on a website, with each containing an illustration, as a triple-decker novel, those illustrations aren’t included.

There’s some exciting shark action from the beginning, with a horse falling off the side and being yummed right up by a Great White. There’s also some premonition, when Vincent falls in a pond and has his toes bitten off by a pike as a boy - he’s not fond of water or carnivorous fish.

The first book is split into two sections, initially setting up the Birkenhead and the people on it and then going into the flashbacks. The second book alternates between flashback and ship-board action and the last book takes place on the ship and the later tribunal. I found the stuff on the Birkenhead to be a little less interesting than the flashback stuff, until the ship struck the rock and things went full throttle.

Jack Vincent is the son of a tailor who was put into the Marshalsea by the oily Mr Grimstone. There his literacy sets him apart and he reads to the other inmates, later creating his own stories. Not only are there Little Dorrit parallels, but the other inmates include the real Bill Sikes and Nancy. One visitor, David (Copperfield) even ends up being Dickens and the two talk narrative and social conscience. One day the prison is visited by Bob Logic, Jerry and Corinthian Tom, the main characters of Life in London, a popular book in the Regency - who are also real life artists the Cruickshank brothers and Pierce Egan.

Shark Alley is full of references, both historical and literary. Publishers, both mainstream and radical are important side characters. Vincent is represented as a keen Chartist, who was present at the mega-meeting in Kennington. He, Dickens and Harrison Ainsworth have a friendly rivalry until the moral panic about Newgate sends Dickens into more respectable territory and Harrison Ainsworth as a less stellar career as a historical novelist. (Carver is William Harrison Ainsworth’s most recent biographer, and a clear fondness enters the text). However, Shark Alley uses all this research to power the story along and there’s never an info-dump quality to it, all research is well digested. Particularly well handled is flash-slang (which I have seen sink other novels) and research into underworld London.

As Vincent is a novelist (he prefers the ‘ebb and flow’ of prose, me too) there are discussions of his novels. Though this is labelled ‘Vol I’, if Carver wants to branch out and write some actual Jack Vincent novels, I am all for them. The Shaking of the Timbers, is a crazy story about time-travelling on a demonically possessed boat that grows limbs. It makes a noble hero out of Captain Kidd and they fight a demonic Blackbeard. I’d love to read that. His gothic novellas include zombie babies born from necrophiliac sex and ghosts coming back to retrieve their gold teeth. There’s also the gonzo take on Sweeney Todd in The Death Hunter - I’m down for all those. There’s even mention of an experimental tale, Jack Sheppard in Space… yes please.

Carver doesn’t shy away from the grotesque. Both his parents meet horrid endings, one by cesarean and the other being eaten by rats. His sister is taken away by a strange dopplegänger and the book suggests a sequel where she is found (yes please). This goriness is brought to full force when the HMS Birkenhead sinks (as it did in real life) in an area of the sea known as Shark Alley. The book is not afraid to make the shark attacks as vicious and violent as possible, even including the literary equivalent of jump-scares. One man has his head bitten off when he looks down into the sea from a lifeboat - it’s great.

Shark Alley develops a very likeable hero in Vincent. He’s had a rough life and has responded likewise, he makes many stupid decisions but he has a young wife and son and it’s clear to the reader how much he has changed for them. It also creates a brilliant villain in Mr Grimstone, who always manages to pop in the book to ruin things. He’s everything wrong with the world, a rich capitalist politician who masks his cowardice under a pretended military service and his perversions under a pretend happy family life. Very hateable.

I’m just waiting on volume 2.