Just here...

Saturday 30 June 2012

Tuesday 26 June 2012

Review: The True Genius of Oliver Goldsmith by John Hopkins

The idea of this review being part of the Goldsmith Season may seem a bit absurd as I wrote those posts many months ago; but if English weather teaches us anything, it teaches us that seasons can be as long or short as they want and can pop up at any weird time. This little moment of Goldsmith is to review the book The True Genius of Oliver Goldsmith by John Hopkins.

The aim of the book is to argue that Goldsmith is more than a gooseberry fool, writing entertaining and easy to read writing of a sentimental bent but actually a sharp and incisive satirist whose writing is written with such delicate irony that it has been misread for two-hundred odd years.

The argument goes through a number of stages. The first is to disprove the notion of Goldsmith as a Sentimentalist and early Romantic, but to establish him with the hard-nosed, rational Augustin tradition that included Swift and Johnson. He does this by quoting parts of his works and correspondence that clearly show him to be on that side of the fence. We are then taken through his early essays and his Treatise on Polite Learning in Europe to further back this point up.

Next he takes us through Goldsmith’s two big poems, The Deserted Village and The Wanderer. It is important to his argument that these poems are read as rhetoric pieces, arguments and not sentimental emotional splurges. He does this by going through The Wanderer and linking it to passages of Aristotle’s Rhetoric.

Then he looks at the Chinese Letters, published as The Man of the World, one of my favourite books. He looks at how Lien Chi Altangi is not a complete voice of reason in the book, how the satire of the book is pointed at his supposedly pure rational character as much as it is at the foolish habits of the English. He also reinterprets passages often seen as sentimental in a way that is satirical and explains that Goldsmith is often writing for a dual audience, one who see the subtle and pointed satire that is presented in a sentimental fashion, and those who merely enjoy at a sentimental novel.

Finally he gets to the crux of the argument, a complete reinterpretation of The Vicar of Goldsmith, a book I recently described as ‘where a man loses everything and learns nothing’. Hopkins argues that this anti-climax is not the result of bad writing but is the key punchline in the book. That through a very delicate layering of language, (for example ‘treasure’ being a term of endearment for his children but also his literal conception of them). He looks at how other critics may have missed the levels of irony, and then teases them out for the reader.

He concludes that satire is a spectrum, from the big bolshy satire of Swift at one end and the sly, ironic, subversive sneaky sort of Goldsmith at the other. He says that Goldsmith is a supreme satirist and finishes the book saying;

“We will no longer think of Goldsmith as merely an amuser but second only to Chaucer as a master of the art of amiable satire”. High praise indeed.

I am one who loves Goldsmith, and have always read those sentimental moments of his writing with a lopsided smile - it is clear that Goldsmith is no Henry Mackenzie and could never have written A Man of Feeling as is view of the world if too tough for that. However, in his zeal for establishing Goldsmith as a proper writer, he forgets all the things that make Goldsmith’s writing so enjoyable. He makes a few off the cuff comments about Goldsmith’s readability but usually in a negative way, that it is his readability that has stopped people reading him closely. Goldsmith’s writing is always clear an enjoyable, not so with Hopkins, who throws terminology around the page, expecting his readers all to be up on their Aristotle and mid-twentieth century literary criticism.

Although Hopkins’s awkward writing style doesn’t detract from his argument for Goldsmith as an important writer, it does lessen the persuasive power of the book. What saves The True Genius from being a dryasdust literary quibble is the pure passion that Hopkins has for his theory. I have never read an academic point of view put forward so vigorously (if sometimes confusingly).

To me, he was preaching to the converted, but to anyone who thinks that The Vicar of Wakefield is merely a bit of fluff, I recommend you re-read it, looking for the sly smile behind the text.

Anyway, have fun.

Yours

Saturday 23 June 2012

A Trip to St Bride's

Today I was lucky enough to go to St Bride’s Church on Fleet Street as part of the ‘Celebrate the City’ events being held in London Town.

Saint Bride’s is known by several sobriquets including, ‘The Cathedral of Fleet Street’ and ‘The Printer’s Church’. There has been a building on the site since the Roman settlement of Londinium (then just down the road) and there have been Saxon, Norman and later medieval churches on the site. St Bride’s was reputedly founded by the Irish saint, Brigid, who reputedly came and formed a well and a church.

Incidentally, Brigid is one of my favourite saints, obviously an Irish saint, she is one of the patron saint of beers and one of her miracles was turning dirty bathwater into beer. A prayer attributed to her begins, ‘I wish I had a great lake of ale for the King of kings, and the family of heaven to drink it through time eternal.’

The tour started with music, written by Henry Purcell for the church. Looking around, the light dances around the building and everything is light and airy. The fixtures and fittings are principally from the 1950s, rebuilt after it was reduced to a husk during the Blitz. The shell of the building is from the 1670s, rebuilt after it was reduced to smouldering ash after burning down after the Great Fire of London. There is a display in the crypt of remnants of two charred bells from the two disasters.

In the corner of the church is a small chapel dedicated to members of news companies captured or killed, while gathering news stories. In this chapel they are prayed for and vigils are sometimes held. Another feature of the church that shows its links with the newspaper culture of Fleet Street is the dedications on the benches, not just dedications to journalists but also benches sponsored by papers and magazines. My favourite being the OK bench.

St Bride’s association with printing goes back to the time Caxton’s successor Wynkyn de Worde moved the Caxton press from Westminster to just outside the church, so he could sell his works to the many monks monking around the area. The guilds of stationers and printers grew out of the guild of the church, linking the two for over 500 years.

Parishioners of the church include Milton and Dryden and Pepys, who was baptised there and buried his brother there (after bribing the warden to nudge other bodies out the way). The crypt was exposed after the bombing, allowing historians to date the church much further back then originally thought and also exposing all the coffins and also a charnel house.

The tour takes us through a basement, where there is a little kitchen, a box of steeleye span cd’s, that the light-fingered muse calls me to steal (I resist) and behind a little wooden door is a pit with bones laid out a criss-cross shape and pretty skulls laid in a row, row, row. It looked pretend, like something created for a cheap horror attraction (of the sort I once worked). It was strange to stand there, looking into the blank sockets of a previously alive human. Momento Mori indeed.

Stranger still was the ossuary. During the rebuild, most of the coffins were cleared away and buried in other places, but 250 of them were marked by having lead plaques on the coffins, allowing the bodies to be identified in the records. These bodies were removed from there coffins, studied and then placed in a little office, the heads stacked tidily on the shelves and the corresponding bodies stacked in boxes nearby. This is where the next part of the tour took us, into a strange office lined in buff boxes, labelled with things like ‘skull and mandibles with hair’ and ‘skull fragments’. Under a desk, with an old IBM on it, are a pile of lead plates with people’s names on.

One of the names is of a man who in his career as master of the Stationer’s Guild and a key eighteenth century novelist, combines many of the aspects of St Bride’s. The man is non other than Clarissa author, Samuel Richardson. I would have given his skull a piece of my mind, but I didn’t know which one it was.

Also buried in the church, but not distinguished enough for a lead plate was Robert Levet, physician to the poor and the subject of one of my favourite poems ever.

On The Death Of Mr. Robert Levet, A Practiser In Physic

CONDEMN'D to Hope's delusive mine,

As on we toil from day to day,

By sudden blasts or slow decline

Our social comforts drop away.

Well tried through many a varying year,

See Levet to the grave descend,

Officious, innocent, sincere,

Of every friendless name the friend.

Yet still he fills affection's eye,

Obscurely wise and coarsely kind;

Nor, letter'd Arrogance, deny

Thy praise to merit unrefined.

When fainting nature call'd for aid,

And hov'ring death prepared the blow,

His vig'rous remedy display'd

The power of art without the show.

In Misery's darkest cavern known,

His useful care was ever nigh,

Where hopeless Anguish pour'd his groan,

And lonely Want retired to die.

No summons mock'd by chill delay,

No petty gain disdained by pride;

The modest wants of every day

The toil of every day supplied.

His virtues walk'd their narrow round,

Nor made a pause, nor left a void;

And sure th' Eternal Master found

The single talent well employ'd.

The busy day, the peaceful night,

Unfelt, uncounted, glided by;

His frame was firm--his powers were bright,

Though now his eightieth year was nigh.

Then with no fiery throbbing pain,

No cold gradations of decay,

Death broke at once the vital chain,

And freed his soul the nearest way.

As on we toil from day to day,

By sudden blasts or slow decline

Our social comforts drop away.

Well tried through many a varying year,

See Levet to the grave descend,

Officious, innocent, sincere,

Of every friendless name the friend.

Yet still he fills affection's eye,

Obscurely wise and coarsely kind;

Nor, letter'd Arrogance, deny

Thy praise to merit unrefined.

When fainting nature call'd for aid,

And hov'ring death prepared the blow,

His vig'rous remedy display'd

The power of art without the show.

In Misery's darkest cavern known,

His useful care was ever nigh,

Where hopeless Anguish pour'd his groan,

And lonely Want retired to die.

No summons mock'd by chill delay,

No petty gain disdained by pride;

The modest wants of every day

The toil of every day supplied.

His virtues walk'd their narrow round,

Nor made a pause, nor left a void;

And sure th' Eternal Master found

The single talent well employ'd.

The busy day, the peaceful night,

Unfelt, uncounted, glided by;

His frame was firm--his powers were bright,

Though now his eightieth year was nigh.

Then with no fiery throbbing pain,

No cold gradations of decay,

Death broke at once the vital chain,

And freed his soul the nearest way.

If anyone does decide to come to St Bride’s, I completely recommend it.

All yours

Wednesday 13 June 2012

Review: The Life of Mr Savage by Samuel Johnson

I was aware of Richard Savage because of his mention in Samuel Johnson biographies and the fact that Johnson wrote a biography about him but until recently I hadn’t followed him in any great degree. This was until I was looking through my anthology of eighteenth century poetry and came across a fragment of Savage’s poem, ‘The Bastard’.

I found the fragment so alive and angry that I downloaded the whole thing. Even the title is a confrontation, I couldn’t take it in to work and leave it on a desk, it was too shocking. The poem begins with Savage swaggering, declaring that a bastard is a vital force, ‘No sickly fruit of faint compliance he!’ He then goes on to boast of the bastard as, ‘nature’s unbounded son, he stands alone’.

The poem goes on to ironically praise his mother for producing him as a bastard. As he praises his mother, the tone starts to become more self-pitying. He starts to lament the lack of care and support, the fact that ‘no Mother’s care, shielded my infant innocence with prayer’. The poem then ends with the mother spurned for a better mother, the ‘Majestic Mother of a kneeling state’, namely, Queen Caroline.

The poem shocks and surprises in its short run, and I was left wondering what extraordinary man wrote such an extraordinary poem?

Luckily an even more extraordinary man wrote an account of his life. Samuel Johnson was a young man, a hack writer and a few years from his Rambler and Dictionary masterpieces. However, this is regarded as a major work of biography in its own right, mainly because of Johnson’s insistence to write about Savage in as fair and humane way as he can. Savage could be puffed up as some tortured genius, better than all those around him; or he could be represented as a pointless, leeching, tramp with a flair for a nice phrase. Johnson treads a line between the two, always weighing the good and bad elements of Savage whilst providing plausible reasons for those characteristics and actions. It is in many respects a very modern biography.

It begins with the typically Johnsonian question of whether the lives of great people are often tragic because great people are more likely to attempt and fail great enterprises; or whether great people have ordinary tragedies that seem greater because we look more closely at their lives. He then to describe Richard Savage’s own tragedy, and main impediment to greatness, the circumstances of his birth.

Earl Rivers - possibly Richard Savage's father.

Savage claimed to be the illegitimate child of Earl Rivers and the then Lady Macclesfield. He claimed that his mother had shipped him out to a nurse, blocked any inheritances his way, tried to get him shipped to America and even tried to influence a court case that would have him hanged. She claimed he was an impostor. The truth will probably never be clear, but what is clear is that Johnson believes the story and Lady Macclesfield is presented as the villain of the piece. What is more interesting is what Johnson does with this information, he uses it as the basis of his whole reading of Savage’s life, telling it as one full of brushes with greatness, almost success but ultimately success frustrated at the last moment.

Even more interesting is how Johnson uses this early, central drama to anchor and explain Savage’s personality. Savage’s inability with money, his pride and haughtiness all come from Savage’s own noble heritage and expectations for himself. The constant rejection from his mother give him the volatile sense of pride that keeps him going during the bad times but topples him in the good. Indeed, Johnson uses the rejection of the mother in an almost modern psychological way, and this helps us warm to Savage and understand him.

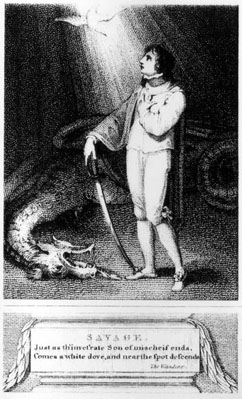

A romanticised view of Savage - as he probably would have liked.

As described by Johnson, Savage is a fascinating man, one who makes friends almost as easily as he loses them. Who can whether great hardship without complaint, but blows up when people try to help him. Who can live on no money, sleeping rough and borrowing from people but can take a year’s worth of wages and blow it in a couple of weeks. Someone who can write incisively and clearly, but lives in a permanently delusive state. All these contradictions are supported in the book by Johnson’s clear and convincing psychological portrait of a man who lives almost completely for the present, and so is happy as long as his present needs are met, and who can waste money in no time.

The story of Savage’s life, after the birth and pointless attempts to win into the family is interrupted by a brawl, where he is convicted for murder. A conviction turned over by Queen Caroline. Savage then passes from friend to friend, using them up and spitting them out. Splitting with his biggest patron because he abused the facilities, and generally being a nuisance, a pest and very good company. Savage then applied for the post of Laureate, apparently being the King’s preference but losing out to our old friend Colley Cibber. Savage then styled himself as ‘Volunteer Laureate’ to the Queen and receives £50 a year from her. He also receives the sniffly response from Cibber that ‘he may as well styled himself Volunteer Duke or Volunteer Lord’. When the Queen died, the money stopped and Savage was sponsored to go to Wales and live frugally. This didn’t work and he died in a debtor’s prison in Bristol.

He seems a strange kind of person for Johnson to write about, even stranger that they were friends. Savage was a dissolute, sponging man filled with pride, who was better at writing about virtue than living it but there was something about Savage’s ability to carry on cheerfully and regardless that seems to hugely impress the neurotic Johnson. Maybe it’s as simple as the answer Boswell received explaining Johnson’s friendship with Dr Levett, “He is poor and honest which is recommendation enough.”

Young Johnson

For a very short book, I had a lot of thoughts, I recommend it to anyone who fancies a rollercoaster ride. I recommend ‘The Bastard’ also.

Yours

Monday 4 June 2012

Review: Clarissa - April - One Month Behind

I was looking forward to the meeting, as always Richardson built and built, until the wait was unbearable. When it came, I was not disappointed.

Richardson, when he was something worth describing, can extract all the tension and cruelness from the meeting, can zoom in on every hurt feeling and sensitive nerve, can recreate the intensity of feeling that can only occur among a close family.

I found Clarissa to be rather cruel, saying she’d rather be bricked up then live with Solmes. I know she wanted to be clear, emphatic and honest, but she didn’t need to be quite so harsh to the poor man. Luckily for Solmes though, he seems rather too dense for the insult to strike really deep.

There were many times in this chapter where I wanted to smack James Jr in the face. Indeed, I found myself shouting at the book for Clarissa to land him one right in the moosh. As often as she says that meekness does not indicate tameness, I am yet to see much of the wild animal in Clarissa.

In general, the book has picked up and I would rather read thirty pages of Clarissa, telling only the events of the 8th of April than five pages of sweeping lyrical history in The Hamilton Case - a book I maintain to be one of the dullest ever written.

Clarissa may be repetitive, it may be in urgent, urgent need of a proper editor, but there is an intensity in the repetition that does propel the book forward. It may be a slog, an arduous read at time and I may be lagging behind, but I’ve not given up yet.

Discover the experiences of better people here

Long to Rain Over Us...

A view of the Royal Flotilla on the 3rd June 2012.

Today, I went to the flotilla on the Thames to celebrate the Queen's Diamond Jubilee. I am no ardent monarchist, but I do like the historical continuation of parades on the Thames.

We were promised a thousand boats, choirs, bells and grand stuff, looking like this.

Unfortunately, it was wet, crowded and rather boring. I was fondled for three hours on the bottom by an old lady trying to push into my spot, I got very humpy with her. The drizzle didn't really stop, but became torrential rain, and the fact is, that a procession of white pleasure boats is rather dull. Never again - thank goodness.

The highlights: Thefirst boat, one with a working carillon of bells on it, was one of the coolest things I have ever seen.

As was the larger one the Queen actually rode in.

The rowing bit at the beginning was wonderful.

There were plenty of moments that made me go wow (though yesterday I went to the 'Making of Harry Potter' Exhibition and wowed even more - the animatronics, astonishing).

Here is a video of the good bits, including the bell-boat in close up and all the Royals.

My little cousin summed up the occasion best with the following picture, which she said is her, waving her flag and smiling while peering through dense rain.

Today, I went to the flotilla on the Thames to celebrate the Queen's Diamond Jubilee. I am no ardent monarchist, but I do like the historical continuation of parades on the Thames.

We were promised a thousand boats, choirs, bells and grand stuff, looking like this.

Unfortunately, it was wet, crowded and rather boring. I was fondled for three hours on the bottom by an old lady trying to push into my spot, I got very humpy with her. The drizzle didn't really stop, but became torrential rain, and the fact is, that a procession of white pleasure boats is rather dull. Never again - thank goodness.

The highlights: Thefirst boat, one with a working carillon of bells on it, was one of the coolest things I have ever seen.

As was the larger one the Queen actually rode in.

The rowing bit at the beginning was wonderful.

There were plenty of moments that made me go wow (though yesterday I went to the 'Making of Harry Potter' Exhibition and wowed even more - the animatronics, astonishing).

Here is a video of the good bits, including the bell-boat in close up and all the Royals.

My little cousin summed up the occasion best with the following picture, which she said is her, waving her flag and smiling while peering through dense rain.

If you look carefully, however, you will see that she is smiling, and I think part of that is pure 'keep your pecker up' spirit, partly the English resilience against drizzle and mostly the fact that she was there with a pretty decent family - as was I.

Tomorrow is a picnic in Hyde Park - Brollies packed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)