Spooks, corpses and other creepy things - maybe it's Halloween.

I come to one of the most curious artefacts in my three-year long search through Leon Garfield’s work, one of his only books specifically marketed for adults, and a book that he didn’t even begin.

‘The Mystery of Edwin Drood’ was started by Dickens in 1870 who wrote six of a proposed twelve serials before suddenly dying from a stroke. The proposed novel is shorter than many Dickens books and seems to be more focused on a mystery than usual for him. For me, the biggest part of the mystery is, ‘how would Dickens have made a surprise from a solution so obviously telegraphed to the reader?’ Although he didn’t leave many notes, he did send someone a letter where he confirmed that the obvious reading of the clues was the correct one…so how was he going to sustain interest to the end? And how does Garfield manage it?

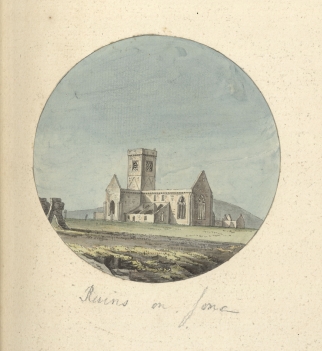

We open with a very striking image of Cloisterham Cathedral that reveals itself to be a vision undergone by Jack Jasper, the lay precentor, as he lays befuddled in a London opium den. As the chapters proceed, we learn that Jasper is uncle to Edwin Drood, who is only a few years younger than him. Drood is an orphan who will shortly be taking his place in his father’s company and become an engineer in Egypt. He is engaged with Rosa Budd, another orphan of rich inheritance, the engagement was decided by both sets of parents before they die and Drood seems to regard her as another good thing he has coming to him. Rosa is less keen on the arrangement, not because she doesn’t like the young man, but because she resents not being given options. The complicating factor is that Jasper has his own obsession with Rosa, signified by a poorly drawn picture of her he has on the wall.

To be honest, I can’t see why everyone is so hot for Rosa. She is constantly referred to as childlike, she has immature strops, she has been coddled for most of her life in pity of her orphaned status (and in honour of her coming wealth). She is cute but she is also silly and stupid, putting her apron over her head to hide her face like a shy child and only being tempted out by ‘lumps-of-delight’ - a far better name for Turkish delight which I am certainly going to include in my vocabulary.

We then spend some time meeting other delightful Dickens characters like Mr Sapsea, a man so vain he creates an epitaph to his wife that celebrates him; Crisparkle, a kindly clergyman with a good heart, a light touch and a rather too close attachment to his mother; and Durdles, a dusty stonemason who hires a small boy to throw stones at him if he stays out after ten at night.

Then enters Honeythunder, another very apt named character, a do-gooder with no good in his heart who drops Neville and Helena Landless at the Crisparkles. They are also orphans but have had a harder time and are fiercer because of it. Neville also instantly falls in love with Rosa (why?) and finds Drood’s lack of appreciation for her disgusting. They have a huge argument.

The next few chapters follow the life of Cloisterham, with Drood and Rosa’s awkward not-really-courtship but they mainly follow Jasper. Jasper makes great pains to be friends with Sapsea, who becomes mayor. He hangs out with Durdles who knows the secret ways of the Cathedral and he confides his fears of Neville to Crisparkle. Then, during a storm, Edwin Drood disappears. Jasper quickly blames Neville and although not enough evidence is found, the town blame him and he has to run to London.

Jasper confesses his obsession for Rosa, who is already terrified of Jasper and goes straight to her guardian in London, Mr Grewgious. Incidentally, I loved Grewgious, he is often (very often) described as ‘angular’, he is so socially awkward he uses prompt cards to get him through ordinary conversation but he clearly has a good heart. He also has Donald Trump’s hair, “He had a scanty, flat crop of hair, in colour and consistency of some mangy yellow fur tippet; it was so unlike hair, that it must have been a wig, but for the stupendous improbability of anybody sporting such a head.”

In London, Rosa meets Tartar, a retired sailor who makes an almost magical roof garden and who Dickens is obviously very fond of (but doesn’t particularly know what to do with). Also a ‘harmless old buffer’ with a secret agenda called Mr Datchery who moves into Cloisterham… then Dickens died.

SPOILER: (Sort of). It is patently obvious at this point that Jasper is the killer, he’s made friends with Sapsea to smooth the way through court and has buried him somewhere secret in the Cathedral, probably Mrs Sapsea’s tomb. This was also confirmed by Dickens. The big question then, is why is it so obvious? While it’s true that the characters aren’t sure who killed Edwin Drood, it’s blatantly clear to the reader.

His daughter thought that the book was more interested in the mindset of Jasper and exploring his nature than a straight-up mystery. Dickens wrote that the anchor of the text was the Bible verse; “When the wicked man turneth away from his wickedness…he shall save his soul alive.” Perhaps the redemption of Jasper was the point of the second half.

There have been many continuations of the story - some where Drood isn’t dead but is Datchery, some where Neville killed Drood and implicated Jasper and many where it was Jasper and he is found out by various means. One continuation was even written by Charles Dickens himself with the aid of a medium. Being a ghost, it wasn’t his best work and the medium’s Americanisms crept in.

Garfield goes the least resistance, Jasper did it route. He makes the drama of the second half less about how Jasper is redeemed and more to do with how he is captured.

Garfield’s style is a pretty good match for Dickens. They share a fondness for odd simile and his comic set-pieces stand up quite nicely with Dickens own. The reading of a play written by Grewgious’s dour clerk, Mr Bazzard is a particular standout, with the clerk’s high opinion of how the event is turning out being wonderfully set against what we actually see. There’s a brilliant joke about the SnakeBite tribe, who only have sixty-five words in their language because they are much higher minded than things like ‘hansom-cabs’ and ‘street-lights’, a fact that most of the characters regard as more inconvenient than noble. There’s a description of a maid who has second sight which is ‘greatly aided by the application of a keyhole’, very Dickensian in its wryness. Garfield also creates a character, Mrs MacSiddons, a retired actress who now runs a lodging house for the profession and regards all excuses to get out of paying rent, even death, as ‘just acting’.

He feels less at home with some of Dickens’ actual characters. His Grewgious is not as angular, his sentences shorter and less awkward and his mode more expressive. Rosa is backgrounded for the (admittedly more interesting) Helena and is not described as the most beautiful woman in a room. He isn’t as in love with Tartar as Dickens seemed to be and the character also fades into the background.

He does love Datchery though. There are some completions of this book where he is really Mr Bazzard, or even Edwin Drood in disguise but in Garfield’s, he is a former-actor turned detective and lives with Mrs MacSiddons when he isn’t investigating. I liked the characterisation, especially the idea that he was tremendously winning actor who can’t remember lines and keeps the name of his alias in the brim of his hat. The inclusion of the stage element, together with some of Dickens’ own Macbeth chapter titles allow for a plan which is telegraphed a little too clearly but convincingly manages to catch Jasper.

Garfield’s Jasper sees (what he thinks) is the ghost of Neville, murdered in a previous chapter. He follows this ghost when he can and realises that it is a real person of flesh and blood. Delighted that Neville is not dead, he feels himself waking up from a bad dream, convinced all the other terrible acts that he has performed were also hideous dreams occasioned by opium. Going to Mrs Sapsea’s sarcophagus, he opens it up with the key he had stolen from Durdles, convinced that there’ll be nothing in it to distress him. Instead he find the mouldering, quick-lime-eaten body of Drood and is arrested.

When Crisparkle goes to visit him in the condemned hold, Jaspers wits are completely gone. He is physically awkward, subject to weird tremors and a double vision. He has psychologically split himself in two; the evil Jasper and the good Jasper. He feels a little sad that he, as good Jasper, will be hanged for evil Jasper’s crimes but hopes for that good part of him to reach heaven. The moment when the noose and bag go over his head are truly moving and we feel very sorry for confused Jasper as he drops. The other characters pair up as they will and it ends with a (mostly) happy Christmas dinner at Mr Grewgious house. The last character is Datchery, who sneaks out of his London house and sets up permanently in Cloisterham as the ‘old buffer’ he was pretending to be.

While I would have liked a bit more of the proposed Dickens plan of focusing on Jasper and his possible redemption, Garfield’s ‘to catch a killer’ second half manages to fit nicely with what goes before it. Garfield’s style is not quite Dickens, it feels alternatively cramped and puffed up - never quite slipping into the ease or ebullience that Dickens possesses. It is, however, a good enough version of Dickens and means that a reader can enjoy the whole story in a far more satisfying way than if they read only the Dickens portion. Perhaps one day I’ll try more Drood continuations to see other ways to end it but for now I’d like to focus on more Dickens, and maybe get another William Ainsworth Harrison fix.