Regular readers of this blog will know I am a big fan of Samuel Johnson and a frequent visitor of the Dr Johnson’s House Museum. One of the things that keeps bringing me back (apart from the complementary wine) is the many exhibitions and events put on there.

The newest exhibition, running until February, is called ‘London’s Theatre of the East’ and was put on with the Arab British Centre which is also in Gough Square. The idea is to look at the relationship between the Middle East and North Africa with London. This also led to a dramatic reading of Samuel Johnson’s only play, Irene, which is set during the fall of Constantinople.

First the exhibition.

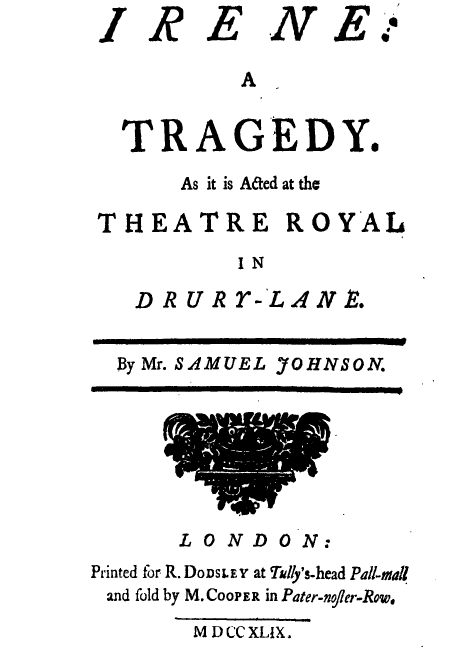

I was delighted to see not one, but two copies of Irene, as well as his Ethiopian set novel Rasselas, the sequel Dinarbas written by someone else and a very rare copy of his translation of Lobo’s book on Ethiopia - the first full book that Johnson had a hand in. I’m a sucker for a book in a case, so these excited me.

More exciting to those around me were the specially commissioned artworks. Saeida Rouass created a piece called Irene Retold, where the play has been cut up, moved about and mixed up with other pieces of Johnsonian text to create a whole different work. The piece uses a technique pioneered by William Burroughs, who got the idea whilst in Tangier. It’s an interesting idea which I only really have knowledge of through pop lyrics.

Most accessible to me (dunce as I am) is the piece The Alcoran of Mohomet’ by Hannah Khalil. It’s a monologue from the wife of a printer who published an English translation of the Qur’an in 1649. The book was actually translated from a French translation and it was fascinating to learn how early any kind of English version was available.

Sultana Isabel by Nour Hage is a large poofy ruff in a range of colours. I later learned that the mannequin is raised to the same height as Queen Elizabeth, or Sultana Isabel, who opened trade routes with the East as a way of avoiding those pesky Catholic countries. The exhibition booklet made some very true and funny statements about how it felt like we studied Tudors ‘on a loop’ at school without learning anything new - especially things like England opening up to ‘Moors and Turks’, as they would have seen them. The booklet also paints a wonderful picture of how confused the Sultan must have been to receive a letter from this insignificant island on the edge of Europe. The bright colours of the ruff are all from ingredients brought in by this trade and examples of those dyes are shown around the sides.

The last artwork is called Ipso(facto) by Lena Naassana. It consisted of photographs of modern British people of various Arabic descents standing with old maps of Arabia projected over them. Some people found it a very moving look at the confused or variegated identities of this people but I have to admit my visual-art-blindness kicked in at this point and I didn’t see much more than some pretty decent photos of people with maps projected on them - a fault that is all my own.

Now the play.

Irene was Samuel Johnson’s money spinner when he came to London. He was going to polish it up, get it performed and make the big bucks as the grand tragedian. Eventually it was performed, more as a favour from Garrick than anything else. Garrick tried to beef it up and make it a bit more dramatic, which Johnson saw only as excuses for actors to ham it up.

When the time came Johnson went to every performance, dressed in the finest clothes he’s ever described it, a gold and scarlet waistcoat and a gold trimmed hat. Garrick’s changes caused a near riot the first night (having the heroine die on stage) so it was changed back to have her die offstage for the rest of the run. The play ran for nine nights, giving Johnson three benefit nights and, with the publication rights as well, was one of Johnson’s better earners. It’s almost never been performed since though and widely regarded as a failure. Johnson was not one to go back to his old work, when he did he was often pleased but when he heard Irene read he left the room because he had ‘thought it better’.

I was keen on seeing what had been cooked up.

A dramatic reading is not a full performance and this allowed the students of Queen Mary University London a chance for some playfulness and wriggle room. This meant that the cast kept interrupting the play and themselves to clarify, discuss and comment on the play as it progressed. It was a little like watching a play with the footnotes on. It was interesting to see some of the parts that were causing the students difficulty (they had problem with the word ‘mien’) and which parts pleasantly and unpleasantly surprised them in the representations of the characters. One of the most surprising things I would have not noticed if it wasn’t for this device, is that the play Irene would pass the Bechdel test, a very simple criteria that many modern works of fiction do not.

As for the play itself, there were many interesting elements. Mahomet was not the usual enraged Sultan (I’m reading ‘Ben Hur’ at the moment and it simply ascribes his outbursts of rage to him being an Arab). Indeed, Mahomet is a rather weak character in the play, talking of love but not doing much. Irene herself was a weaker character than I expected, not putting up so much of a fight before trading religions and becoming Sultana. I think the big problem with the play is that it’s a tragedy in which the title character, the one who inevitably dies, is not one we spend all that much time with.

The most interesting character in the play is Aspasia (played originally by Susannah Cibber). She’s strong willed, sticks to her faith and motivates a lot of the action. She gets away scot-free with her lover Demetrius, carrying the burden of Byzantine culture - if she had died, we’d have had a tragedy. Irene dying is a minor mishap and, as almost no-one else dies, the tragedy simply has no destruction or catharsis.

The lines are heavily metrical, in a strict iambic pentameter which can wear on the eats a little. He does vary this sometimes though. Like Shakespeare, the last two lines of an act rhyme, he also makes far more use of alliteration than he normally does, bringing little pricks to the ear. There were sprinkled through the texts some lines that caught my attention, I only managed to note a few.

Someone fears to wear a ‘rapprochement of chains’.

A daydreamer ‘wanders the fancies of my mind’.

And a war creates a ‘labyrinth of sound’, which I think would make a great album title.

Ultimately the play is not a resounding success but I enjoyed engaging with it alongside the enthusiastic performers and very glad I went.