A Last Gasp of Garfield

It’s happened. I’ve reached the last six books by Leon Garfield. These include the books I found hardest to find and the ones I was putting off reading. From here on, every time I read a Leon Garfield book, it’ll be a re-read.

The Captain’s Watch

The second book in the Boy and Monkey series written for the ‘Long Ago Children Books’ for Heinemann. This series fascinates me with its aim to create good historical fiction and was clearly a success for a while, reviewed in the Times and other national publications but now completely unknown. The first book was a fine little story, although probably too ambitiously written for smaller children but too short for older ones. Unable to find this book, I read the third one, which was unfortunately racist.

The Captain’s Watch is fortunately not racist but like the first book, it’s a very slight story bolstered up by some great writing. I loved the description of the ship “taking in water like the Captain’s Wife took in lodgers” - with a hint that lodgers can also be read as lovers. I liked the cynical captain and his distaste of the hymn-singing Germans that make the boat “so blessed, they’d sail to heaven with a fair wind.”

The story itself deals with Tim and his monkey, Pistol who are being transported as indentured servants to America. Pistol can’t help his training and keeps stealing shiny objects, including the captain’s watch and Tim has to find creative ways to not be hanged from the yardarm.

It’s slight and funny and, unlike the sequel, there’s no use of the ’n’ word.

The God Beneath the Sea

This was a joint writing project between Leon Garfield and Edward Blishen, brought together by their childhood love of Greek Myths. The idea is to take the myths, tie them together into something of a through-narrative and tell them in a language that is gritty, modern and poetic. The book won the Carnegie Medal and Charles Keeping’s creepy illustrations were commended for the Greenaway Medal.

That aim to be gritty and poetic threatens to overwhelm the book but thanks to a smart way with a simile or a dash of humour, it never is quite subsumed. There’s no clear indication of who wrote what, but comparing the crusting on a crab’s shell to mini travelling cities can only be a Garfield idea. I also enjoyed the way the book creates its own epithets for the Gods and Goddesses.

The God beneath the sea is Hephaestus, son of Zeus and Hera, thrown to the sea for being ugly. The stories of the Earth’s creation and the Titanomachy are told to him by the sea nymphs who have taken him in. It’s interesting though, Hephaestus is not really the main character, if anything, it’s Prometheus.

I didn’t realise that in Greek creation myth, humans were created, not by an Olympian but the Titan, Prometheus. What’s more, the human soul are seeds born of the primordial chaos of the world. People in this book are so fragile and weak compared to the Gods and Prometheus sacrifices himself to fight in their corner.

This is very much a God’s-eye view of the Greek myths, dabbling in ones that I knew less about. Not only the lesser told stories of Chronos and the war with the Titans but also the ancient Greek version on the universal flood myth. Also - I didn’t know the walls of Troy were built by Gods.

This is a very different book from Leon Garfield’s others (except the sequel) but it’s vivid and exciting, certainly better than the Stephen Fry retellings.

The Golden Shadow

Whilst I enjoyed Leon Garfield and Edward Blishen’s first jab at Greek Myths, The God Beneath the Sea, I actually felt this sequel was better.

It had the same intensity as the first book, the same skipping and playing with language but the stories were tied more closer together. First, the book tells the stories of heroes, particularly Hercules and secondly, that the point-of-view is lower than the previous book, dwelling with the people and particularly one storyteller.

The storyteller is elderly at the beginning of the book and starting to doubt his belief in the wondrous stories he’s been telling. By the end, he’s even older and even more cynical. He has so many narrow misses with the Gods, demigods and sprites he tells about, almost meting Thetis, almost seeing Prometheus chained in the mountains, coming close to meeting Hercules but not realising it, until one day he meets Hermes, the psychopomp sent to lead him to the Underworld. There’s an interesting through-line that his life actually has a great purpose unbeknown to him which he eventually fulfils. I really enjoyed the sense he had of living in a post-God world even as he lived in the time of legendary heroes.

One of the other things the book does really well is to contextualise the labours of Hercules, not as noble or heroic acts but as penance for a moment of murderous madness. It made him a more interesting person, a sunny person of super-human power tethered by guilt to serve people lesser than him - ending up as a court jester in drag before being stirred from his malaise.

In many ways this book is more of the same for people who enjoyed The God Beneath the Sea but it has a tighter format, is more grounded and I found it more engaging as a result.

The Baker’s Dozen

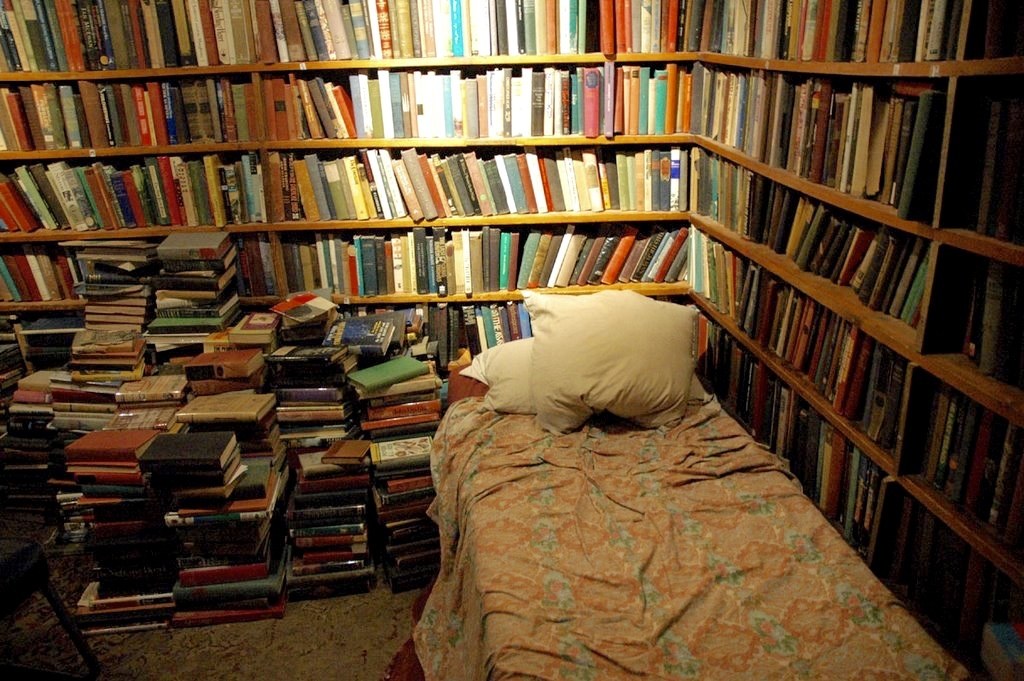

This is a collection of short stories that looks like is was commissioned at the same time as Leon Garfield’s adult compilation, The Book Lovers. It contains short pieces by a range of writers including one by Garfield.

His story, Strange Fish is (typically) set in the eighteenth century and is about a father and son who come across a strangely empty village. The story takes in vengeful ghosts and vicious smugglers, ending in a rather sharp and uncomfortable ending where the villagers who wrecked ships from the cliffs failed the test and weren’t redeemed. Typical of Garfield, it also has the most striking first line of them all.

Edward Blishen, the former schoolteacher who co-wrote the Greek myths books gives the rules of a rather weak Geography/rhyming game. Philippa Pierce (of Tom’s Midnight Garden fame) gives a half decent slice of being-a-kid-in-the-seventies life, Alan Garner writes a creepy story featuring ghouls and broken promises and Joan Aiken offers a creepy story about a woman that gets lost in some alleyways in a fictional part of London and ends up in a Jazz-themed version of hell.

Iona McGregor tells a fun story about an eighteenth century maid hoodwinked into stealing shirts for her lodger, Jill Paton-Walsh takes the reader on a viking journey full of omens and ghosts and Helen Cresswell paints a silly picture of a show-off who deserves a comeuppance. My favourite story may have been The Pergola by William Maine, a story of a crush that has a lot of personality and charm.

The stranger pieces were John Rowe-Townsend’s piece about the difficulty in being a journalist where Tom Hutchinson, a pop journalist who writes an imaginary interview with a poor performer who has been forced into his unnatural life.

I enjoyed all the stories in this collection to a certain extent but the real jewel of the piece is Leon Garfield’s introduction where he goes full tilt at children’s publishing, describing the majority of the books written for children as having ‘the stringency and bite of a wet nappy’. His argument is that once, books were just books and now they are being pigeonholed for ease of sale - I imagine he’d not have been very keen on the YA genre, even as he’d have been placed in it. It’s a good collection though and an interesting snapshot of writing for older children in 1971.

Scripts for Animated Shakespeare

I have a copy of Garfield’s scripts for the Animated Shakespeare series but didn’t read them as I recently watched them all. I found the scripts to be good abridgements of the play which either sung or were let down by their animation style.

Shakespeare Stories & Shakespeare Stories II

I shall review these together as they are essentially two parts of the same thing. The only real difference is that I have read/seen/performed in all the plays in the first set of Shakespeare Stories but some of the second set were new to me.

The difficulty I had with these stories, is that the plot is often the weakest part of a Shakespeare play. People don’t see Shakespeare for the stories but for the characterisation, the wordplay, the construction of individual scenes that give actors the opportunity to give their all. What Garfield does fantastically well is tell the story, whilst integrating the key lines from the play in an organic way - these are really good Shakespeare retellings but I can’t get all that much from a retelling

The thing I found most interesting was the way Garfield brought out the themes of a play and settled on an interpretation on the stickier elements of certain plays. I’m not sure if they were his own interpretations or the most neutral ones, I suspect the latter.

So Twelfth Night emphasised the themes of madness and sanity, something which Shakespeare seemed very concerned about (that and poisons that feign death without being death, there’s a lot of those). King Lear had fun with the pre-Christian nature of the story and The Tempest revelled in the subversion that lies at the heart of the text, it’s a coming-together story more than a forgiveness one. The Merchant of Venice walks the tightrope of sympathy with Shylock whilst The Taming of the Shrew tries to construct a genuine love affair out of the horrific events of the tale, he also makes a valiant attempt to tie the Christopher Sly subplot into the rest of the play.

Where the retellings worked best for me were the plays I didn’t already know - and the one I had seen but hadn’t followed, which was Measure for Measure. It was interesting to see what the play was actually supposed to be about. It was also interesting to see how little Cymbeline is in Cymbeline. How violent and slapstick Comedy of Errors is, and just how many times Shakespeare does the old ‘swap cloaks and be seen as someone else’ deal.

In and of themselves, these are good retellings of the plays but I was only reading them for completions sake.

And there it is, all Leon Garfield’s works read and reviewed… where do I go next?