I picked up An Anatomy of Laughter by Richard Boston from the cheapie section of my favourite bookshop because I like the ‘anatomy’ approach, using lot of different sources to tug and pull at a subject. When I looked at the book closer and saw there were whole chapters about Laurence Sterne and Samuel Johnson, I was very glad I had.

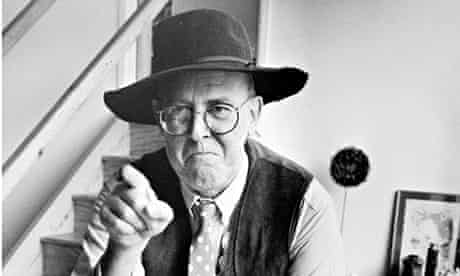

The book was written in the 1970s by an eccentric journalist who launched Britain’s first eco-magazine and was also a large part of the campaign for real ale, despite the fact he preferred gin. Looking up his obituary before reading this book, an ex wife said he was always laughing and was the only person she had ever known who’d woken himself up with his own laughter. The sources and attitudes in the book are a little white guy with a classics education but are livened by the genial, generous attitude of the writer.

He starts off with a chapter where he describes how the current era (the 1970s) has a rather queasy laugh and how some have declared it the end of humour and comedy. To be fair, though some sitcoms from the 70s still hold up okay, there is much of 70s humour, such as the club comedians, which have not aged well at all. In contrast, now (in the 2020s) comedy is in rude health, at least if that health can be judged by the swarming multitude of stand-ups I’ve never heard of on panel shows. Boston plays a switch on the reader though, discovering similar write-ups on the ‘death of comedy’ going back for years and years. Rather like music, it seems that many individual’s taste for comedy deteriorates as they grow older and each generation feels like things aren’t as funny as they used to be.

The next chapter is about the physical expression of laughter, mostly using early-modern medical textbooks as Boston seems to enjoy watching people of the past groping towards more accurate physical knowledge. One theory is that the lungs act as bellows, blowing the spirit of life through the body in laughter.

Then there’s a chapter on theories of laughter. These are mostly pretty grim. Plato thought that laughter was caused by the sudden feeling of superiority over another person, whilst Hobbes agreed and included the notion of feeling superior over a past self. A man called Bergson said that laughter policed the lines of conformity, when a person crosses that line they are laughed back into submission. These are all laughter as a form of attack and control which Boston says misses another aspect of laughter, the one based in the joy of play and pretend. There’s the laughter at pure inventiveness, silliness, fun - even the more attack-based laughter of a stand-up comic bantering with an audience is aggression that takes place in a suspension of real life, a kind of pretend. He concludes that the things that make us laugh involve aggression, obscenity or playfulness, often in combination.

The book then looks at different ways of making people laugh. There’s a chapter on mediaeval fools (which I read a few books about in 2019), one about slapstick and the silent comedians (he’s a Buster Keaton fan more than Chaplin, as he thinks the sentiment disables the laughter). There’s a chapter dividing wit (which yokes two dissimilar ideas together in a persuasive way) and humour (which involves the comic observations on the frailties of the human species). Incidentally, France tends to pride itself on wit and Britain on humour, though both have had examples of each. None of what is said is particularly original, I’ve heard that comment about Chaplin many times, but they are nicely put.

The book also has a great time in finding examples of wit, humour and such to give to the reader. Some of these I had heard of, like Spooner telling the student he’d ‘tasted the whole worm’ or the very funny textbook English as She is Spoke. Others were new to me, like the witty vicar, Sidney Smith, who could dissolve a room into tears of laughter, or Daisy Ashford, the nine-year-old author of a grown-up society novel, The Young Visiters.

Then came the case studies. The first was Rabelais, whose work I was planning to read this year anyway. It gave me a good grounding in Pantagruelism, ‘jollity of mind, pickled in the scorn of fortune’ and made me rush the book right up in my reading plans. Another was about Shandeism, emphasising how Tristram Shandy has not lost its power to tickle, antagonise and amuse readers - I’ve read it before but I’m reading it with my book group in April.

Another case study was Samuel Johnson, who seems like an unusual choice for a book about laughter to the uninitiated, though when Johnsonians get together and talk about him, there’s often laughter. Unfortunately, the chapter doesn’t really talk about how funny a writer he can be, it’s not about Johnson as a comic but as a laugher. Many accounts of him describe how his long, insistent laughter was quick to arrive, long to stay and could cause other people to laugh even if they didn’t know what he was laughing at. I was reminded of the Tom Davies quote that he laughed ‘like a rhinoceros’. Boston also made the point that Johnson often laughed at very small things, whether it was the rats line in Grainger’s Sugar-Cane, or a friend making his will. Johnson’s huge laughter was equal to his huge depression, a vital boost in his battle against his own melancholy feelings.

The next chapter ran with this idea, talked a lot about Byron and talked about a book called The Savage God by by Al Álvarez, mostly about Sylvia Plath but also about a Romantic obsession with suicide. He slices that idea right down, emphasising the laughter among the Romantics, saying that the doomed Byron is the least interesting, and not very accurate.

“Johnson and Byron experienced life as something disorderly and irrational, that needed the disorder and irrationality of laughter to make it bearable.”

This book, while in many ways a scrapbook of quotes and (slightly worn) anecdotes does manage to be a fairly enlightening look at laughter from physical, emotional and cultural perspectives. It is also frequently funny, Boston having a good turn of phrase himself, and good at bringing the reader to other funny things. Ultimately it proves the point he quotes from Scottish poet, Norman Cameron, that laughter is ‘the sunlight in the cucumber’.