Iona McGregor was recommended to me by one of my favourite authors, Leon Garfield, in his collection of stories, The Baker’s Dozen. He describes her as “a new writer - and fresh as a daisy” whose works are “as sharp at witty as one could wish.” Her story in the actual collection, Macfadyen’s Shirts wasn’t one of the standout stories but was a fun little thing about a conwoman who steals shirts drying on the bushes outside Edinburgh. It looks like she was set to become a name in children’s literature but her work becomes a succession of study guides.

According to Wikipedia, her career as children’s teacher and writer were hampered by her sexuality and after she quit teaching, she put more of her energies into LGBT advocacy, as well as being able to write a few books with explicit gay content. She wrote study guides because they paid well, lectured for the University of the Third Age and helped form a group called AD - officially called Anno Domini but for those in the know, actually called Aged Dykes.

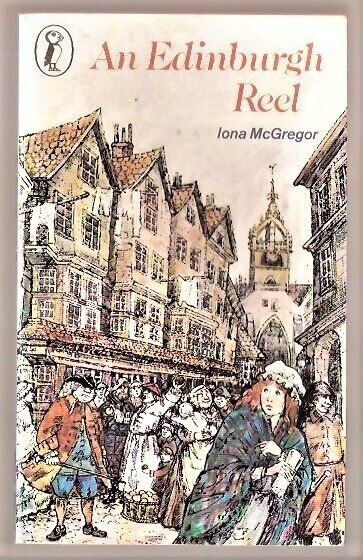

I decided to read An Edinburgh Reel because the anniversary of Culloden is coming up and I have a number of Jacobitey books I wanted to get round to.

Set in Edinburgh in 1751, Christine Murray is approaching adulthood and looking forward to a happier future. Her Father, the brother of a Laird, fought in the ’45, escaped to France and has spent six years as a soldier in the court in exile. Having received a pardon, he’s returned to Scotland with the hope of winning his old land back. She hasn’t seen him since she was nine and the cross, bitter old man is not the father she remembers. It turns out that he hadn’t merely escaped after Culloden but had been betrayed by somebody and spent a year in a hulk-prison, before escaping that. He has scores to settle and is obsessed with discovering the identity of his betrayer.

The relationship between father and daughter is really well drawn. It’s clear that they were the apples of each other’s eye before the ’45 but the younger daughter has worked through the trauma and poverty of defeat and is ready to make her way in the new burgeoning Scotland (represented by her fancybit, an idealistic law student). Her Father is stuck in the old ways, convinced that the only work for a gentleman is farming or inn-keeping and also convinced that he is still a gentleman. His bitterness and lingering resentment also serve to pull the man down whenever it looks like he may adjust. He is baffled by her acceptance of the new normal just as she is frustrated by his inability to accept how things are. Even better, these characters aren’t trapped within these world views, she begins to understand how her father must face his past just as he begins to be more flexible and even enjoys making use of his language skills as a clerk.

Their distant cousin, Lord Balmuir serves as the symbol of the new, Whiggish Scotland. He has a Robert Adams house which “looks as bizarre as if Lord Balmuir had erected a Hindu Temple in his fields.” He also does the signaturely Whiggish thing of growing new trees on his estate, and most English of all, turnips. He has no time for crofters, only wishing to have long-term tenants who’ll farm in the modern, scientific method. He’s also heavily into the linen trade, wishing to grow it on Scottish shores. Remarkably, he’s not the baddy. He offers Christine and her father all the help he can and, when he has very good reasons to punish them, continues to help.

The plot involves a shady agent, who wishes to rope Christine’s father into using Balmuir’s linen contacts as a Jacobite postal service. It also concern’s Christine’s romance with the law student, which is hampered by the subterfuges she must give to protect her father. Finally, it’s about finding the person who betrayed her father, with the main clue being a snuff-box which once belonged to him. The twist is pretty obvious and could be guessed from even this loose recount.

What makes the book great is the depiction of certain things I’ve not seen in other eighteenth century historical fiction. There’s the tense build up and release of a theatre riot, an amateur cockfight, a depiction of the genteel but cramped highlife of an Edinburgh tenement and a game of golf in the snow. (I found the position of the caddy really interesting, similar to the London Porter but hireable for any kind of odd job - including following people in this book). I also loved how the book highlighted what a cultural shift has happened between 1745 and ’51, with a real sense of that earlier conflict being less about English and Scottish, but old ways and new ways - with the new ways clearly in the ascendence.

The book also used a lot of Scottishisms, my favourites being; weesht, tauchle, camsteerie, gey, tirl, fash, quaich, smeddum and (best of all) clishmaclaver.

A short novel, ostensibly for children, An Edinburgh Reel managed to fit some interesting looks at eighteenth century life and a discussion of the new ‘enlightenment’ Scotland with a group of interesting characters (and one scene-stealing pig). The plot is a little rushed and the twist obvious but it’s exciting and memorable anyway - especially for its length and intended audience.