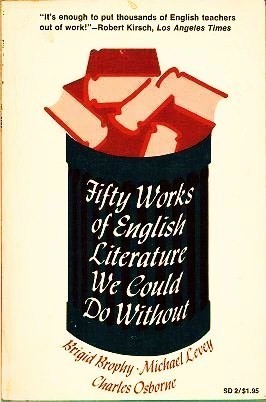

Last week I looked at the book Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without by Brigid Brophy, Michael Levey and Charles Osbourne. This is a book where a iconoclastic trio propose works that don’t need to be in the British and American canon… some of which no longer are. They also take some pot shots at eighteenth century works.

In the first part I looked at the novels, now I am looking at plays - and it starts with a biggie.

She Stoops to Conquer by Oliver Goldsmith.

They start by referencing how Goldsmith himself was good with children. Then they say that this play is to facile for even the “most naive adults” who would not even find it “tolerable”. They then laugh at a professor in Leeds who called it timeless, which suggests to them, “how slowly things must move in Leeds”. They concur with Walpole that the play is stiff and contrived, clumsy and graceless.

The gruesome gang then go on to pick on Goldsmith himself. They say that at his heart there’s “an uncertainty about how to harness the creative power to any distinct purpose”. They say he dithers over whether to pick up a “scalpel or powderpuff”, never finding the right tool for the job, being torn between being Voltaire and Rousseau and so not really being anything.

They then talk about how likeable Goldsmith is as a person, that the play is as likeable, which is what makes it a poor work of art. They propose that while they want to keep him as a man-of-letters, it’s more generous to keep him and his life and to ditch his work.

I think they fundamentally misunderstand Goldsmith’s writing. It’s not that he dithers between his sharper Voltaire instincts and his softer Rousseau, it’s that he does manage to blend both within his writing. He was widely read in contemporary French literature (and often lifted parts wholesale) and I think was aware of mixing the biting and the stroking, often hiding one behind the other. His ability to write hurried Grub Street compilations that became standard works for centuries is a prime example of how well he could shape material for an audience. He’s more readable and likeable than many of his peers yet is able to slip in real jabs and ideas as well.

I think She Stoops to Conquer has rather dated though. He set out to write, and succeeded in writing a ‘laughing comedy’, there are funny bits in it but having seen a recent-ish production, it is a little creaky now. However, most comedy ages badly, and for it still to more-or-less work three-hundred years later is a sign of quality.

Yet, it’s not my favourite Goldsmith. I think he should definitely remain a standard man-of-letters but his reputation could stand on The Vicar of Wakefield and his essays, particularly The Citizen of the World. Perhaps this is just a me thing, I’m not sure how well those works would go down now, but I really think Citizen of the World is funny, representative of the time and even tells a pretty decent little story as well. She Stoops to Conquer may seem like a slight work, and Goldsmith a slight author, but we’d lose much without him.

The School for Scandal by Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Another writer they prefer for his personality than his writing, they say that the existence of The Rivals and School for Scandal would have been better as lost works. If they hadn’t survived, the writers argue, Sheridan could be hailed as the continuation of Congreve and the pointer to Wilde but as they stand, one is “clumsy and unconvincing” and the other is “neat and unconvincing”.

His big problem is that he aspired for jeux d’esprit but “tamed his jeux” until all that was left were “limp artefacts utterly lacking in esprit”. They say he was too timid and unwilling to offend that his “always tiny talent” was minimised into even less. They suggest that modern audiences are now robust enough for Congreve and Vanbrugh and no longer need this watered down version.

I can’t speak too much for Sheridan, I have read and seen both The Rivals and The School for Scandal and I like them both reasonably enough. Although I’ve read Congreve’s little novel, I’ve not read and seen his or Vanbrugh’s plays, so I couldn’t tell if Sheridan is simply a watered down version. What I do know, is that Sheridan borrowed many of his comic situations from his mother’s novel, and I plan to read that at some point.

It’s not that I take the remarks of Brophy, Levey and Osbourne too seriously, there’s is a fun game to play and I’ll have to think of fifty ‘classic’ works that I’d be happy to bin and why. I’m sure they had a great time writing this book and can imagine them in a pub, arguing over the choices and trying to top each other over who can say the rudest things. It is also funny how few of the books mentioned are still central pillars of literature, oddly I’ve put some things on my reading list because of the trashing they got in this.

No comments:

Post a Comment