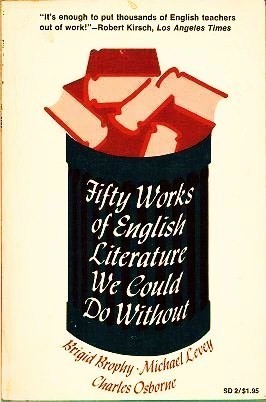

Fifty Works of English and American Literature we could do without presents itself as the work of three enfant terribles, taking a sledgehammer to the self-satisfied corpus of English Literature. It caused a stir in 1969 but is mostly forgotten now.

Written by three authors, the best known at the time was Brigid Brophy, which is how I came to this text. I remembered the quote “To my mind, the two most fascinating subjects in the universe are sex and the eighteenth century” and I looked up who said it. This led me to Brophy and her own fascinating body of work, which put her on my list of authors to keep my eye out for. This book was one of the most eye-catching titles on that list and I found a copy on the internet archive.

Skimming the contents, it’s interesting how many of the works poked at aren’t great beasts of the canon any more. I’d not even heard of The Dream of Gerontius, or The Essays of Elia, even as I am aware of the authors. Oliver Wendell Holmes is not a name I’ve ever heard of, nor his book The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table. Some of the other ‘great works’ in this book have rather lessened in stature. Of the big books in here that are still big, some are prodded just to show gutsiness. The pages on Hamlet can’t declare the play to be worthless, only to overshadow some of Shakespeare’s other work.

The book is arranged chronologically, with a few pages being given to each dedicated work, arguing why the book can be done without, the flaws in it and (sometimes) some worthy alternatives. It’s a book I’ve mostly skimmed through, but I think it may be fun to go through the eighteenth century books mentioned and see what I think of the conclusions. I’ll start with the two novels picked out and, next week, I’ll look at the two plays.

Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe

The first eighteenth century work given the Fifty-Works etc treatment, it starts off by comparing Defoe-Fielding-Smollett as a housing estate of red brick, solid buildings, something unexceptional but functional. Then it argues that Moll Flanders is not particularly functional, containing the “thinnest trickle of narrative”. It says that although the novel catalogues the events with nothing left out, nor does it “put anything in” with a sense of morality and characterisation that is “stunted”. It describes his prose as “clean” but “inept to novels, since it swallows all the vividness of what it recounts into itself”. The section on the book I sonly a page and a half long, given poor old Defoe short shrift.

To be honest, I’d agree with the criticisms of Moll Flanders and of Defoe in general. I’ve said myself that his journalistic training and journalist’s prose are very good at reporting processes (like Robinson Crusoe’s house, or Moll’s own stealing) but less successful at conveying emotion. In my video on the ITV drama of Moll Flanders, starring Alex Kingston, I said that the real benefit of the screen adaptation was to dramatise the emotion that a reader of the book has to imply. However, there is a case that Defoe’s emotional flatness gives space to the reader to ask what they would do in the circumstances. It also has to be remembered that one of Defoe’s big aims in his novels was verisimilitude, the flat, reporting style of them make them seem true - to such an extent that it can be hard to forget that Moll Flanders was not a real person. (I’ll be reading a very intriguing book about Moll Flanders soon).

Tom Jones by Henry Fielding

Now the iconoclastic thrupple go after my favourite novel. It starts off with a very long-winded paragraph describing a Kipling novel called Stalky & Co, in which a boy feels like something less because he isn’t sporty like the titular Stalky. It suggests that Tom Jones has been popular for years because it stands as the one example of a book that isn’t wet and weedy, “Tom Jones has become the accepted epitome of red-bloodedness.”

They agree that the book Tom Jones is vigorous, but that Tom himself isn’t. He’s a “tom cat of remarkable passivity”, who is more flirted with than flirting. But that’s okay, his blankness is typical picaresque stuff, it must be the adventures that are vigorous. The gang argue that the adventures aren’t, just a series of bed-hopping and bonks on the head. They also say that the other characters aren’t all that interesting, that they all have their one thing, something it calls a “sandwich-flag system”, presumably that the flag allows you to know exactly what the sandwich is.

Brophy and co claim the vigour of the book all comes in the narrator, a narrator who they say doesn’t really want to narrate, writing introductory material right up to the end. They say Fielding isn’t all that bothered telling the story, presenting the actual events in a “clerk of the court way”, that is might not be “quite as dull” as Moll Flanders, but goes on twice as long. They say the book doesn’t convey the sights and smells of eighteenth century Britain, and that Fielding as narrator spends the whole time convivially slapping you on the back, leaving the reader, “as aching and bruised as they would have been had they spent the time playing rugby.”

As much as I love Tom Jones, I have to agree that he is a weaker element of the book. He does the job fine, but he is a little bit of a blank slate for the reader. I whole-heartedly disagree that the side-characters aren’t brilliant though. Squire Western might not be a complicated man, but he is a fun one to be with, enlivening any scene he is in. As is his sister, as is Honore the maid, or Partridge, or any number of the folk in the book. I think Sophia is a character that a reader can genuinely fall in love with, possessing a fascinating range of emotions and ending the book on her own terms. If they are a little simplistic, they are in the way that Dickens would later make his characters, and they are vigorous and memorable for that simplicity.

What’s more, I think the characterisation of Fielding’s narration completely wrong. How could they describe it as “clerk of the court”? There are whole chapters written purely ironically, there’s an arch play in every part of the book and the voice is what makes it truly compelling. Even the part they quote, which is intending to show Fielding’s bloodlessness is a beautiful play of mock heroic classical allusion and quotidian truth. I’m afraid the gleesome threesome are utterly off here.

Next week I'll look at how they rate Goldsmith and Sheridan.

No comments:

Post a Comment