Saturday the 2nd of December at Dr Johnson’s House. The temperature has dropped rapidly, everyone has discovered their hats and scarves and Gough’s Square is full of people hunting down the twelve snowman statues of Christmas. As busy as the square is, none of them are coming into the museum. It’s a little too cold to sit and read so I go into the parlour where the powder closet is open.

The powder closest was originally built as a place to powder a wig but may never have been used for that purpose. Certainly, Samuel Johnson wasn’t known for the upkeep of his wig. Now the museum uses it as storage for books, prints and items for the shop. However, there are two plastic tubs on the top shelves labelled ‘LB1’ and ‘LB2’. With nothing better to do, I decide to get them down and have a look.

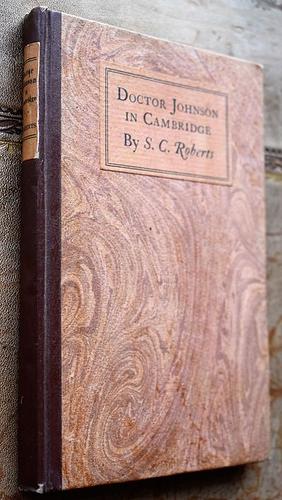

The boxes consist of library overspill. Second copies of things the museum’s library already has mixed with doctoral dissertations and other odds and ends. There’s a copy of the wonderful Samuel Johnson; Detector, the first in a series of four collections of detective stories starring Boswell and Johnson. The library has a copy signed by the author, this is just a spare. There’s a Samuel Johnson edition of the Bookseller magazine from 1903, there are monographs of various quibbles and details, and there is Doctor Johnson in Cambridge, a true oddity.

I pick the books I most fancy reading at some point and put them in the cellarette, a small cupboard designed for storing tea and coffee which now sits behind the desk I sit at when welcoming visitors (and taking their entrance fee). This cupboard is already full of modern books that have accumulated but I feel that it’d be a better ‘look’ to have the Johnson books behind me, plus I can read the ones that have caught my attention.

For the rest of the morning I read Doctor Johnson in Cambridge. It was written by an Sydney Castle Roberts and published in 1922. In 1923, this copy was given to someone called ‘The Hol Punch’ by someone called ‘Thomas Blue Bell’ in memory of the 34th anniversary of their Charterhouse days.

Describing itself as ‘essays in Boswellian imitation’, the book consists of eight little sketches, with five of them having previously been published in The Cambridge Review. The book is small, the font is large and there are only sixty roughly cut pages. The premise of the sketches are to imagine that Johnson, Boswell and a number of other figures from Johnson’s life find themselves visiting Cambridge for various reasons, giving Johnson a chance to satirically assess Cambridge university of the modern day (or at least the 1920s).

Johnson in the modern day is an idea that pops up a fair amount. Julian Barnes gives him a cameo in England England, it’s sort of the premise of Marcel Theroux’s Strange Bodies and I even had a whack at it on my website, where Johnson became a couch potato and binged episodes of Top Gear. Here, Johnson opines about Cambridge Universities debates about allowing women to receive degrees (something they didn’t until 1944), watches a rag week and a modern game of cricket and even meets a major who’d gained renown due to his action in the First World War (in which the author himself fought at Ypres).

Like most depictions of Johnson (According to Queeney excepted) he is mainly created by taking various famous quotations and stitching them together in different ways. The ‘young dogs’ he wishes to frolick with are the Cambridge students, the Labour party are ‘the last refuge of an idler’ and he calls for student beer to see ‘what makes an undergraduate happy’.

Roberts shows himself to have a pretty deep knowledge of Johnson, especially the Johnson of Boswell’s Life. He remarks to a market stall bookseller that he once refused to man a similar stall. From this bookseller, he also buys a copy of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy and announces it as the only book that’s ever prompted him to get out of bed two hours earlier. (I’ve often wondered about that, why couldn’t he just read it in bed? I know I did.)

Roberts also characterises Boswell pretty well, from his giddiness at seeing Johnson in different situations to his own sense of ego at being Johnson’s confidant. He rather over-eggs Johnson’s jokey antipathy to the Scots, with most of the sketches bringing up something or someone Scottish for Johnson to rag on. There’s also a running joke about how Johnson sees himself as an Oxford man and rather runs down the Cambridge students for being less rigorous in their studies and generally more into boozing and partying.

What is most interesting/needling, is what Roberts imagines Johnson’s view of the modern day would be. In some aspect we are in agreement. If he’d seen a Cambridge rag week, I’m sure he would have been won over by the high-spirits eventually - he was always a sucker for youthful hi-jinks. Similarly, I agree that would have enjoyed a modern (well ‘20s) cricket match for its formal as well as athletic elements. However, I do find it hard to believe that Johnson, who was a big arguer for women’s education and helped designed curricula for Hester Thrale’s daughters, would have argued against women gaining a degree. Still less would I imagine he’d have had an instinctive ‘yuck’ reaction to women as he seems to in this book. Nor can I imagine Johnson arguing against the idea of liberty as he does in the chapter on the Cambridge Union. Roberts reuses the ‘yelps for liberty’ line from Taxation No Tyranny many times in odd contexts.

I think this book, short as it is shows two particularly interesting things. One is how the scholarship around Johnson has changed since the 1920s, biographies and studies pull from a wider pool than just Boswell and as a result, Johnson is a more fragile, thoughtful man. Not just the blustering rhinoceros (as seen in Blackadder for example) but a man with a warm, if sometimes needy or self-pitying heart. There’s also the interesting way people use Johnson to reflect their own times. The Johnson we promote in the house was a supporter of intelligent women, an early anti-abolitionist and a holder of frequently liberal views - for Roberts he was a stalwart, not only of old Toryism, but the conservative party of the 20th century.

It’s interesting and a reminder that while the real Johnson was only himself, the image of Johnson is one that can revived, refreshed and refracted in many different ways.

No comments:

Post a Comment