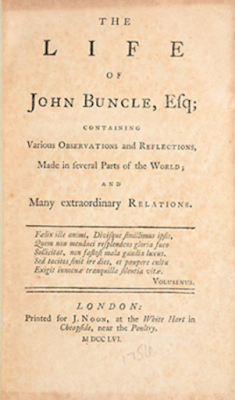

After 750 pages of The Life of John Buncle, Esq, I thought I was Buncled out. Even the temptation of DE Stevenson’s Miss Buncle’s Book would not draw me to Buncle again. But then I saw John Buncle Junior, Gentleman by Thomas Cogan - maybe I can stretch to a little more Buncle.

Despite claiming to be written by a son of the original Buncle (of Miss Dunk, if you were wondering), it’s a very different book, rather more like one of Richard Griffith’s books, one of which is named in John Buncle Jr. Rather than being a meandering mix of religious screed, encyclopaedia and romance, it’s a fairly typical set of light eighteenth-century essays with a loose theming around sending letters back to a fancy—bit while taking a trip. Personally, I love this kind of thing and many eighteenth-century authors were so good at creating a likeable, conversational personality on the page.

But how? Older Buncle made it clear that his children were losers. “They never were concerned in any extraordinary affairs, nor ever did any remarkable things that I heard of; only rise and breakfast, read and saunter, drink and eat, it would not be fair, in my opinion, to make anyone pay for their history.” Younger Buncle says that his esteemed father, though a very good man, is too argumentative in his views and lost contact with all his children as they become less vehement than he.

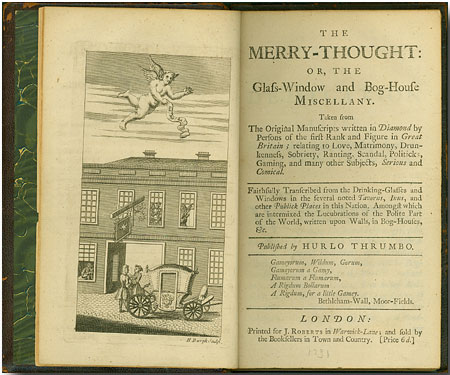

The first essay is about the title. The publisher doesn’t think that John Buncle Jr, Gentleman is not a very catchy title, that he could at least prop his name up with a ‘learned’ or ‘renowned’. The publisher says that he likes a teasing, vague title, as, “Our business is to catch attention and the less we reveal, the better chance for a sale.” He says these vague titles are especially good for scrappily written, miscellaneous works and he cites the name Something New, one of Richard Griffith’s books under the name of Automathes. He also has a list of sellable book titles to slap onto future books. These include;

“The mental Don-Quixote

The spiritual light-horseman

The moral hussar”

- I just found those funny.

The first few chapters poke light fun and play with many different parts of the book, the title, the pitfalls of a dedication and the throat-clearing of the preface. They have that wonderfully light, snarky and direct tone often found in these kind of pieces. The sort of writing that shows how readable older works can be, that verbose and stiff writing is not a necessary feature of old writing.

The next chapters purport to be letters from Buncle to Masie, the woman he loves, as he takes a little saunter around the home counties. He says that he is travelling sentimentally, meaning that he is travelling with his eyes open to the little moments and stories as he goes. The rest of the book are these little events and thoughts he has to himself.

The first goes a bit Wonder Woman, as he possesses a ‘whip of truth’, a device that allows him to see beyond the outward impression and into the reality of people’s lives. At other times he refers to it as his ‘rod of intelligence’ and his ‘mystic instrument’. He touches people with this device, sees the seemingly innocent maiden who yearns for her lover again, the pious vicar who is simply totting up his tithes and other stock hypocritical figures. Of course, the only person who is straightforward, and is not kidding himself about his qualities or happiness, is the poor street sweeper. He was press-ganged away from his family, lost a leg and returned to find his wife dead and his children scattered to the winds. To be fair, his happiness mostly consists in the knowledge he has nothing to lose, and the appreciation of the things he has.

There’s one pair, an old man with a young schoolgirl, which prompt a little more investigation. He is an aged family man, who takes the girl for a little fling in return for presents. She is the daughter of honest farming people who has been sent to school to improve her prospects but which has essentially corrupted her by false promises of her eligibility in fancy circles. Her preferred lover is the school dancing master, but she’ll fool around with the old man because he has better gifts. Buncle notes; “One incident made me smile. In the ardor of his caresses, the upper set of the gentleman’s teeth fell into her lap.” I laughed at that.

As they get closer to London, the chapters discuss that city. He talks about the hypocritical poets, who write about the better moral purity of the countryside when they couldn’t exist outside of the metropolis. He tries to set a case for London, describing the kind of people who might get something out of the place. These include pleasure seekers, men of business, criminals, single men who enjoy the freedom and those who are “able to embrace a thousand miseries if they appear but happy” - i.e influencers. He doesn’t exactly succeed at selling London, not with the certainty of Johnson’s overused quote. He says that true Londoners think they are wiser and sharper than everyone else but would be useless anywhere else. He also defines those Londoners as those “born within the sound of Bow Bells”, which is the earliest version of the classic Cockney definition that I’ve read.

On the way, he finds himself in a manky inn. They climb up to the central dining are where the naked spaces of the room let the imagination work at will”. I like the idea of him seeing faces in the cracks of the walls. I also wonder of there’s any graffiti there. The landlady has an amazing ability to talk all the time and Buncle wonders how she does it.

“I will not say she thought aloud; that would be paying her too great a compliment; but every drifting idea that slightly touched upon the fibres of her Censorium, immediately ran by something of an electrical conductor, to her tongue, and set it into motion.” It’s a neat little character sketch.

Then there’s a chapter which describes a series of people taking offence at small trifles, then the book simple stops. There is no conclusion, no reunion with Maisie, no sequel. That’s it. So that’s also the end of this write-up.