I feel I stick to the theme pretty well on this blog, but sometimes I like to write about a book just because it particularly caught my attention.There are not many 12th Century Arabic texts that are translated into English with references to Jeremy Beadle and lines where a character promises to shank another character’s nan but this is not an ordinary translation.

Al-Harīrī wrote a sequence of stories called Maqāmāt in the twelfth century, in some part as a response to another series of stories by a man called al-Hamadhānī. The original stories were about a beggar who uses his eloquence to get out of trouble and win money but Al-Harīrī went further with the word games and verbal tricks. Despite being a respected and enjoyed work for almost a thousand years, it’s long been regarded as untranslatable and for good reason, the text is so tied to Arabic as a language that there are hard decisions when translating into a language as different as English.

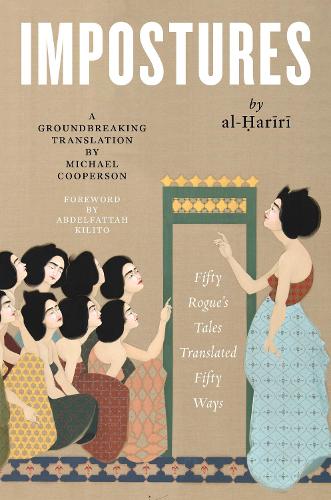

The person making these decisions is Michael Cooperson and he decides that Maqāmāt, which he names Impostures, is primarily a celebration of Arabic as a language, revelling in its oddities, quirks and special tricks. For this reason, his translation into English aims to celebrate what makes that language special. This informs most of his choices. Maqāmāt is largely written in rhymed prose, something that English has trouble with, so the choice is made that each of the fifty stories are written in a different form of English. Each of the different impostures are told in different ways, there are jargons like business slang, criminal slang or the language of psychoanalysis; some are told in the style of authors including Chaucer, Joyce and Lewis Carroll - and others are told in world Englishes like Singlish or Naijá.

This means that reading Impostures is like reading four books at once, the original Maqāmāt, the English version, the type of English that Cooperson has chosen to imitate and then an essay about each story at the end of it. The essays are a very important part of this text, tying the other three parts together and mediating between the reader and the original Arabic text. I’d love more translated works to have a proper essay at the end where the translator discusses how they went about their work - it’s a fascinating thing to think about.

What’s really impressive about this, is that the aim of Cooperson was to do as correct a translation as possible, only frequently not into standard English. If the translator’s essay is correct, the translation follows the original quite closely, even translating specific turns of phrase - it’s not a loose rendering like Coleman Barks’s Rumi, for a start Cooperson can read Arabic. The text is also littered with references from the Qur’an, which are all explained.

Johnson happens to be only the writer imitated twice, it seems like I shall never get away from they guy (not that I particularly try). Other eighteenth century writers imitated include; Henry Fielding, Lord Chesterfield, Daniel Defoe and of course, flash slang. Being pretty comfortable with the original texts of these authors, I feel I can judge Cooperson’s approximations, and to be honest, they aren’t very good. The essays afterwards show that a lot of work went into each one, there’s a lot of reading involved and they are scrupulously checked that the language of each one comes from texts by the given author, to the extent that the odd word that isn’t, is explained later.

Despite the work put into ensuring accuracy, they don’t have the same sort of rhythms, they don’t feel like what they’re supposed to be. The Johnson texts use groups of threes, latinate vocabulary, lots of Johnson features but they don’t feel like Johnson. However, I don’t feel that this is a weakness of the translation as much as the text being pulled in too many directions. As well as feeling like Johnson, the text has to be an accurate translation of 12th century Arabic - it’s an impossible task and to succeed as much as it does is an impressive feat. (Not to say anything of the sermon that could be read forwards as backwards, the paragraphs with no ‘e’, the ones that only had ‘e’, the puns riddles and homophone games - which were all pulled off wonderfully).

Despite the work put into ensuring accuracy, they don’t have the same sort of rhythms, they don’t feel like what they’re supposed to be. The Johnson texts use groups of threes, latinate vocabulary, lots of Johnson features but they don’t feel like Johnson. However, I don’t feel that this is a weakness of the translation as much as the text being pulled in too many directions. As well as feeling like Johnson, the text has to be an accurate translation of 12th century Arabic - it’s an impossible task and to succeed as much as it does is an impressive feat. (Not to say anything of the sermon that could be read forwards as backwards, the paragraphs with no ‘e’, the ones that only had ‘e’, the puns riddles and homophone games - which were all pulled off wonderfully).

The tales told in other kinds of English were more successful to me. Although they were too crammed with slang, they were fun to read. I’m pretty good with Cockney Rhyming Slang (which gave the Jeremy Beadle reference) and Multicultural London English (which talked about shanking a nan) to be able to read without the glossaries. The joy of these sections was the element of subversion, a nine-hundred year old text ‘should’ not be translated in this way - but why not? What is more correct about translating into Standard English than other forms?

As for the tales themselves, they are fun stories about someone using language to overcome people of greater power and status. Abū Zayd is likeable for all of his untrustworthiness, mainly because he is playful and fun-loving, it’s always a joy to read about a trickster. For original readers, there was an added subversion to the tricks he plays, as these tricks are all with Arabic, the language that (for Muslims) is the only human one God ever deigned dictate a book in. That this holy language has inconsistencies that can allow someone a life of trickery, is a fun concept.