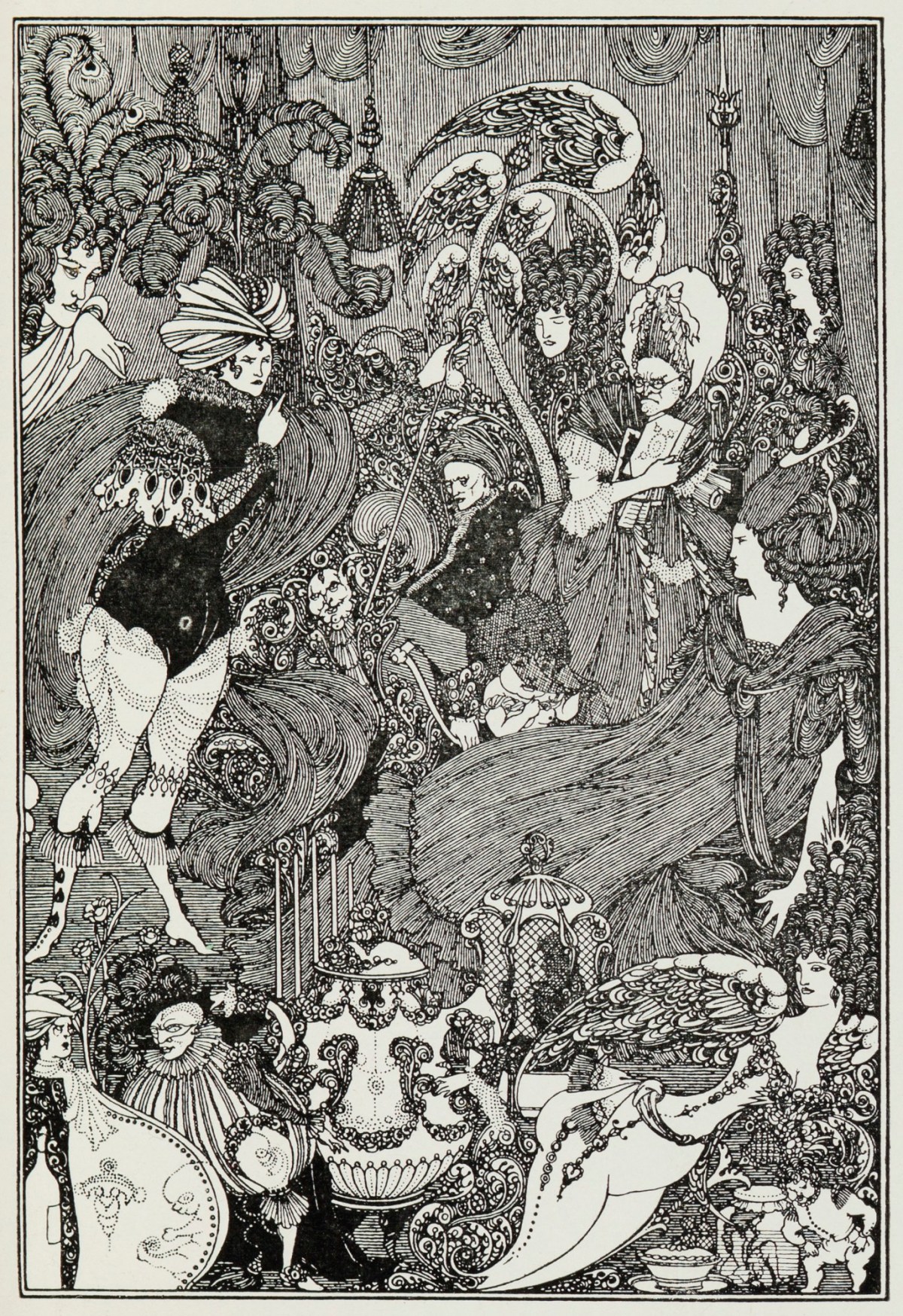

I picked up Sophie Gee’s The Scandal of the Season shortly after watching the first series of Bridgerton and it looked like similar campy, arch, nonsense with its Aubrey Beardsley cover and a detachable fuchsia face-mask. It’s not that. The blurb implies that the novel is a risky love story tied up with a Jacobite mystery but that’s more the subplot, the main story is about young Alexander Pope.

It’s strange, the story of young Pope, an outsider from high society because of his mercantile and Catholic background, further marked out by his illness and hunch-backed body, is by far the more interesting element in the book and downplayed by its cover. Pope (or simply Alexander, as the book frequently calls him) is a charming character, a little gauche and naive, with a deep ambition to be a great writer but a touching doubt that his talents won’t be enough to secure success. He’s far from the snidey, aggressive author of The Dunciad, having published a few pastoral poems that he’s afraid will lead to him being labelled as a sweet, country-born bard. His Essay in Criticism is about to come out and his principle emotion is worry, particularly that he will be attacked by the critic Dennis, who he’d later eviscerate as ‘The King of Dulness’.

The novel itself starts with a priest being murdered, starting a running sub-plot of Jacobean plotting. It’s frequently off to the side of the novel, with certain characters slipping away during society functions to share warnings and packets of money. Interestingly, this is a plot, but not a Jacobean one. It’s a scam run by a dodgy sometime slave dealer who is playing on the high-emotions of the Jacobites and the need for secrecy to cover the scam. I really enjoyed this little twist, so many books have the Jacobite plot in them, from Moonfleet to The Virtue of the Jest and it was nice to have it play out a little different.

Ultimately, the book is about recontextualising the event that prompted Pope’s Rape of the Lock. Within that poem, it was a pretty simple act, that a Baron cut off the lock of hair from a beauty because he wanted her so badly. Lord Petrie was the Baron and Arabella ‘Belle’ Fermor was the lady. Throughout the novel they have an illicit affair, starting as public flirting but becoming a private and sexual affair. This also allows Belle to have access to more exclusive social circles, which she revels in but it’s clear the two are in love with each other also. It does also mean this novel does have some fairly explicit love scenes and references to Rochester’s poems and visual pornography. It doesn’t make this book the bonkbuster it seems to have been marketed as, those scenes are few and the focus does seem more on Alexander Pope then this romance. When Petrie’s family discover and disapprove of the affair, they can leverage Petrie’s foolishness with the Jacobite stuff to make him publicly break off their secret engagement by stealing her hair - so the ‘trivial act’ of the poem is not as trivial as it first appears.

I really liked the dramatisation of Pope’s relationship with the Blount sisters, Teresa and Martha. The eldest is trying to ape Belle and enter her circles, the younger is aware that she’s not the kind of person to seek attention. Pope is romantically infatuated with Teresa but he is more drawn to Martha as a person - the three were going to have a complicated relationship for the rest of their lives.

There’s also depiction of Pope’s first meetings with Swift and Gay, lifelong friends (though largely by letter) and members of the Scriblerus club. There’s even a glimpse of how they bounced ideas off each other as they jokingly create an ‘unlearned’ club while chatting during an Italian-style opera. Swift even points out his own ‘savage indignation’, a description he’d have engraved on his tomb, though he does laugh at one point, something he was never reported to have done. Apparently he barely even smiled.

This book is set in a world where most social encounters involve verbal jousting. It might make the book seem a little odd or stiff at first but once acclimatised, it was interesting how well character was established through these formalised conversations. Pope has a skill at simile and comparison but often pitches his conversation too humbly or boldly, Teresa has a habit of being a little sharp, Arabella a little too insouciant. For the most part Lord Petrie pulls it off perfectly, but he has the confidence of title, cash and good looks to do so. That does mean it is genuinely shocking when a character ditches the social game and says exactly what they thought, and these moments were sprinkled well throughout the book.

Ultimately, I thought this a really decent novel about a young man of talent but little social standing making his first entrance into a highly stratified social world, with some romance, plotting and sex to provide some contrasts. I think it should have been more clearly marketed as what it was, as it would disappoint those expecting a campy sexfest or a thrilling Jacobite novel.