William Betty first came as one of the side-stories in Andrew McConnell Stott’s The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi. At the turn of the 18th century, both society and theatre was extremely chaotic, leading to all sorts of fads. There were fads for ‘aqua-dramas’, which took place on flooded stages, a rise in speciality acts, a number of celebrity dogs - and there was Bettymania.

Rather like Beatlemania, Bettymania created huge crowds but unlike Beatlemania, people died in Betty’s crowds. There were duels, not even about whether Betty was a good actor, but about which role he fulfilled best. For just over a year, the whole of the UK were obsessed with one actor, someone who played all the main roles in Shakespeare and beyond, playing Hamlet and Macbeth in the same year, and was only 12 years old.

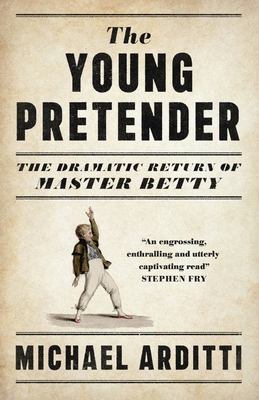

When I picked up The Young Pretender, I thought, for a moment, that I was picking up a biography but this is a novel. Set a few years after his heyday, the now 21 year old William Betty has decided to make a comeback. He navigates the difficulties of returning to the theatrical world but also comes face-to-face with the memories of his former life as a supposed prodigy.

Betty is a very engaging character, trying to hang on to his dignity, having to remind everyone he meets that he is ‘Mister’ now, not ‘Master’. He has very little arrogance about his former dominance, hyper-aware that he is meeting fellow actors at a far more even level than he was in his superstar years. He hopes that his maturity will have improved him as an actor and is not blind to the idea that he was never a great actor so much as a fad. True, it hurts him if other people tell him these things, but they are not new ideas to him. He also holds a truly sweet and naive hope that, with work, he may become the actor he was previously hyped up to be. It’s charming how he amuses his little sister, tries to connect with old friends and just tries to be a decent professional, without becoming despondent by the increasingly clear ambivalence that audiences have to him as an adult. He also weathers a number of comments about his increased weight with aplomb.

There’s a lovely scene where he meets up with Dora Jordan, ditched by her royal partner. The two reminisce, not about life on stage but about the time she took an exhausted Betty and let him recuperate at the family home. There’s also a very good scene where Betty decides to be ‘a man’ and sleep with a prostitute. It just so happens that the one he picks up saw him on stage a few years earlier and she remembers it as one of the high-points of her life. Not wanting to ruin her memories, he gives her the money and leaves with the deed undone.

The biggest problem with the novel is the matter of amnesia. Whether it’s because of suppression, or the drugged up haze a lot of his acting career was performed in, but Betty has almost no actual memories of his time in the spotlight. These memories leak in as the book progresses, with Betty and the reader discovering them at the same time. The trouble is, this element of the book tests disbelief too hard. There is no way Betty wouldn’t be able to remember whether his tutor, Gough, sexually abused him or not. Nor is there anyway he couldn’t remember a certain ‘fan’ certainly tried to until the end of the book. Betty’s access to his own memory is plot-convenient in a way which breaks realism too much.

Were I to write a book about William Betty, I’d have been tempted to write a farce. The notion of a boy taking the central male roles in popular plays and playing them against adult casts (indeed, adult love interests and antagonists) and it being phenomenally successful, is a farce. Michael Arditti has chosen to write a drama, however. This is probably fairer to Betty, who ended his own life following a second unsuccessful comeback but it does mean the book is a fairly drab affair, full of disappointment, hazy memories of parental abuse and possible child abuse. What’s more, the character of adult Betty is so passively accepting of what has happened to him, his realisations are met calmly, until at the end he decides to kill himself (an attempt which failed, incidentally).

As such, Arditti probably respects the historical Betty more in his dour telling but didn’t give me all that much joy.