Pope’s The Rape of the Lock is a poem I’d read before but I reread it in advance of reading a novel about its creation called The Scandal of the Season. The version I read was the 1717 one in the student Twickenham edition.

In the introduction to this version, Pope claims the original version was printed against his will when he hadn’t finished writing it. How many times did Pope pull that stunt? With his letters, he even cheated a printer into publishing it before turning on him in print for doing so. He says that in his new version, he has made Belinda less like Arabella, the woman who actually had her hair snipped off. He also says he’s added Machinery, an equivalent to the muses, dryads, Gods and Goddesses of classic poetry. These come in the form of sylphs, a notion he’s nicked from the Rosicrucians.

Famously, the poem is about “What mighty contests arise from trivial things”, in this case how a man cutting a woman’s hair led to her being upset. The tone is mock-heroic, in which the small details are described in the full lusciousness of epic poetry. I have to admit, I now find this poem extremely camp, and the sylphs don’t help.

We meet them swirling in the air, enacting all the pleasures and wishes of ‘polite’ society. They are Belinda’s dreams of all the things she’s hoping for in life but it’s presented as a grand vision. A vision with a warning of darkness in it. Belinda then gets up and puts on her make up. I many ways this reminded me of a tooling-up scene in an action film, these are her weapons and she plans to leave the house well-armed. There’s also a theme of prayer as she performs the “sacred rites of pride” that “calls forth the wonders of her face”. It’s almost like she, herself is a chief priestess but the vision in the mirror is her goddess.

We are then introduced to the villain, a Baron who is besotted by Belinda’s hair and is determined to take some. It reminded me a little of the episode in Casanova’s life, when he gathered the hair of a woman he was ‘in love’ with and turned them into sweets that he’d eat as he tried to seduce her - he actually failed that time. The Baron has his own altar, one to romance built of twelve French romances. However, if The Female Quixote taught me correctly about those books, they would not have suggested stealing hair, a hero would have been banished from his loved one for decades if he tried that.

There is a lovely (and very camp) description of Belinda going in a boat to the party, surrounded by her sylphs. They are described as fairylike, fluttering in many colours, with butterfly-like wings glistening. There are also hundreds of them guarding her, many around her skirts, many around her head and the chief one keeping an eye on her lapdog, Shock. She arrives like an invisible fairyland.

Those same sylphs then help Belinda win at cards. It’s described as being “combat on a velvet plane” and the cards are anthropomorphised into warriors, battling it out. The image of the cards physically duking it out was fun and seemed almost Alice in Wonderland to me. Belinda is not a quiet winner either, she shouts and hollers when she wins, a hint of her actions to come. Then the Baron approaches with his “two edged weapon” as she is looking into her coffee cup.

It’s actually a tense scene, with Pope repeating the word ‘thrice’ as the Baron steals himself to cut her hair. As he slices, he cuts a sylph, no need to worry though “airy substance soon unites again”. He cuts her hair and Belinda immediately screams, leading Pope to wonder how her hair has the sensation to let her know it’s been cut.

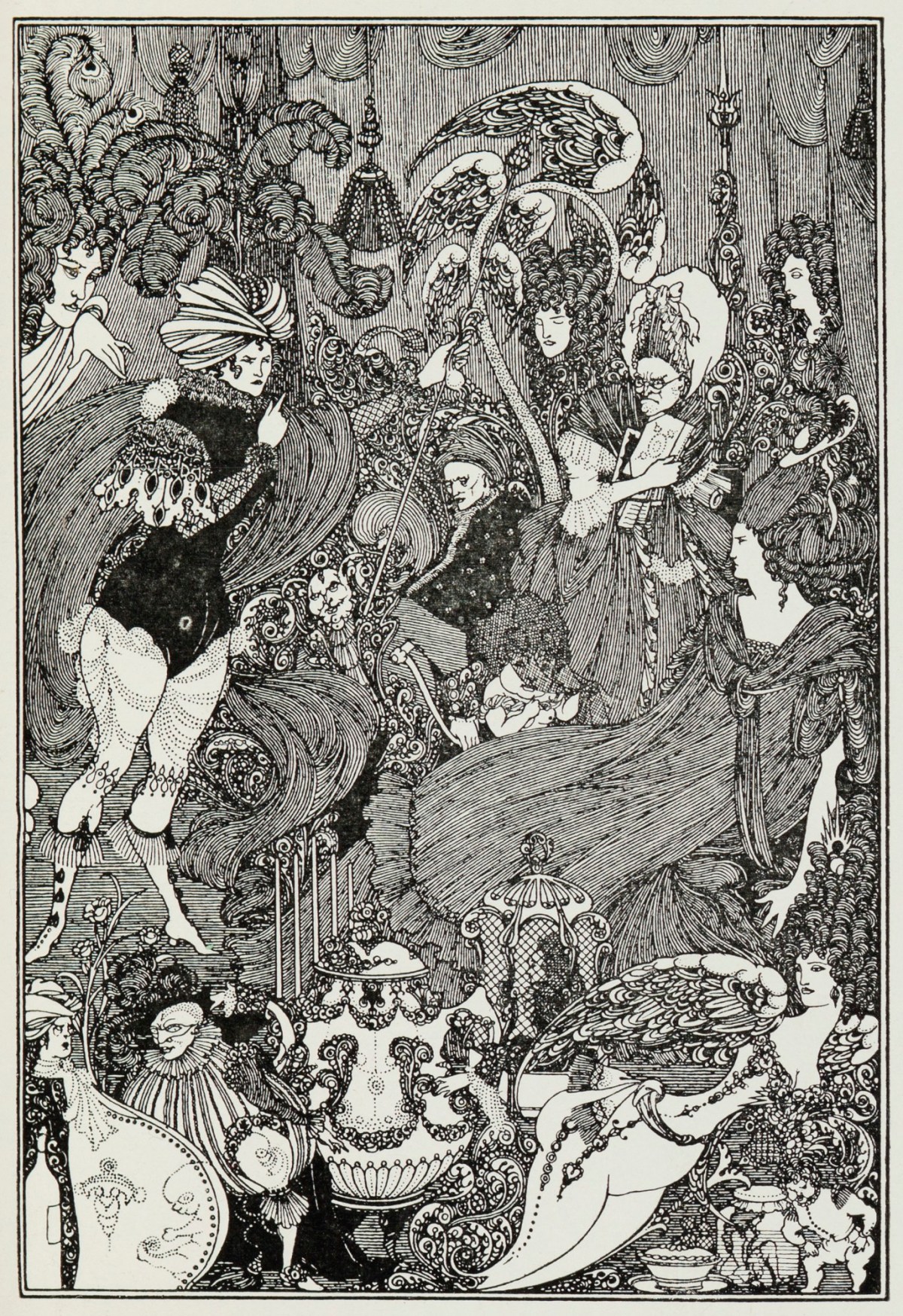

The next canto is the ‘Cave of Spleen’, which is pure camp. I may partly think this as I have a copy of Aubrey Beardsley’s illustration of it on my toilet door but the text does include living teapots and Mrs Potts is a camp icon. It’s essentially a psychedelic representation of a bad mood, especially the bad mood of someone who’s a little dramatic. She complains to her dad, who speaks crossly to the Baron in sweary cliché, a speech described as speaking “so well”. Belinda mourns the lock of hair, wishing she’d never been to the party and had been a hermit.

The sylph Cassandra then comes and give the moral of the piece, it’s a crap moral. Essentially Cassandra argues that Belinda should cheer up, it’s only a lock of hair and that no men are going to like her is she seems melodramatic and fussy. I, however am rather on Belinda’s side. It really is a terrible invasion of space to cut someone’s hair without warning. I know the title uses the word ‘rape’ as part of its mock-heroic style, but there is a line crossed there for me. Luckily, everyone ignores Cassandra, as people always do.

Belinda goes into battle, first by shouting and giving dirty looks. Men “die in metaphor” in those angry eyes, it’s a massacre.. sort of. Then she takes some snuff and shoves it up the Baron’s nose, incapacitating him, something I definitely stealing for something I write sometime. She gets the pin out of her hair and is prepared to jab him with it when the hair becomes a comet’s tail, being placed in the sky for all to see and admire - like the stories where heroes become constellations.

I found it odd the poem ends there, we never actually find out the resolution of the conflict. In real life the couple’s engagement was called off. I really enjoyed my re-read of this poem. It has a cartoony, technicolour quality and I enjoyed it as an (inadvertent?) example of high camp. I look forward to seeing what a novel does with the material.

No comments:

Post a Comment