In 1773, a sixty-two-year-old Johnson and a thirty-odd-year-old Boswell went on a trip they had been playfully imagining for ten years. They travelled up to the Hebrides in an effort to see what was left of the old Highland way of life. Both of them wrote a book – and Dr Johnson’s Reading Circle read both of them.

Johnson’s A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland was published first. In many ways, it’s a traditional travel book, with Johnson describing the key features on the way and often measuring them. He then makes his conclusions and opinions on what he sees and hears. The book is arranged by location, with the odd gallimaufry of discussion and opinion in various parts.

Coming out after Johnson’s death was Boswell’s The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides. Whereas Johnson talked about Scotland, Boswell talked about Johnson. Written up from his journal of the trip, Bozzy published the book to test the waters and try out the style of his proposed Johnson biography. There’s lots of conversation and little details that would have been lost to time.

Of the two, the group overwhelmingly preferred Johnson’s account and even found it easier to read than Boswell. Discussing things as inconsequential as scenery with Johnson makes his quite a relaxing book to read but there is a wellspring of anger just underneath. Famous for being disparaging to Scots and Scotland, he quickly finds himself warmed (if not always inspired) by the people’s company and flattered by their welcome. What shines through is his disgust at how parts of Scotland were not looked after or developed – not a disgust at the people, but in how they are being let down by their leaders. This disgust comes through his frequent astonishment at the lack of trees, the poor quality of the housing and the huge swathes of people emigrating to America. There is many a deserted village.

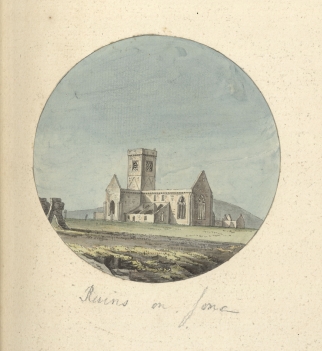

There is also the quality that has him called a ‘secret papist’: his dismayed reaction to the seemingly endless array of destroyed churches that he sarcastically describes as ‘a triumph of reformation.’ This is not, I think, out of any real Catholic sensibility, but more from a general reverence for churches and land deemed sacred. His paragraphs about the ruined abbey on Iona are worthy of the praise Boswell gave them in his own book.

Turning to Boswell, there is a problem with his seemingly compromised Scottish identity. Proud of his ‘old blood’ and deeply in love with the romantic ideal of the Highlands as he is, he is also a Lowland Scot and a member of the modern, forward-looking Scotland. Where he has to shift between identities throughout the journey, Johnson can just be himself. There’s also the element of him ‘auditioning’ his ideas and style for Johnson’s biography to fellow Johnsonians. Boswell sees himself as made greater by this adventure which ties him closer to Johnson’s ‘brand’. There are moments in the book that are painfully, toe-curlingly, embarrassingly, Boswellian.

Despite this, we learn a lot we would never have found out otherwise. We learn that Johnson has read Castiglione’s The Courtier; that Johnson has ‘often’ imagined what sort of seraglio he might run and has considered how he would fight a big dog; that Boswell was once encored for his cow impression in Drury Lane, and that Johnson is pretty good on a horse – if it’s a decent size.

We also enjoyed the amount of teasing in the book. Boswell teases Johnson about old lady who thinks Johnson’s question of ‘where do you sleep?’ is a come-on. Johnson teases Boswell for staying up sharing six bowls of punch. They take turns teasing each other over which of them is the wenching ‘young buck’ and which the civilising influence. At night they often share a room and have private conversations in Latin so their discussion can’t be understood through thin walls.

Then there is the full description of their visit to Flora MacDonald and the narrative of Prince Charles’ escape from Culloden. This part is worth reading the book for itself.

Taken together, the books present a fading existence with compassion and anger, but also present a long road trip in all of its highs and lows. Whether it is Boswell feeling superior as Johnson is seasick, or Johnson riding the prow of the boat as Boswell is seasick, this journey cemented the friendship of the two men, gave them quality time together and laid the seeds for Boswell’s later biography.

There was a lot of Scottish travel experience amongst the group, with many having been on parts of the journey and one member having undertaken the whole lot. Even in the modern era, roads flood, ferries are cancelled, island supermarkets run out of food and the mizzle, drizzle and rain pour constantly.

Our boys didn’t make their journey alone. As well as meeting helpful lairds, old women, reverends and servants on the way, they were accompanied by a trusty guidebook, Thomas Pennant’s A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides (1772) Johnson admired his guide and frequently leaves the descriptions of geographical to him. Currently Dr Johnson’s House have an exhibition, free with entry, that explores the relationship between Pennant and Johnson and includes copies of their books and numerous contemporary artworks of the places visited.

I recommend anyone to give these books a go and to see the accompanying exhibition: there’s much to enjoy as we discovered for ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment