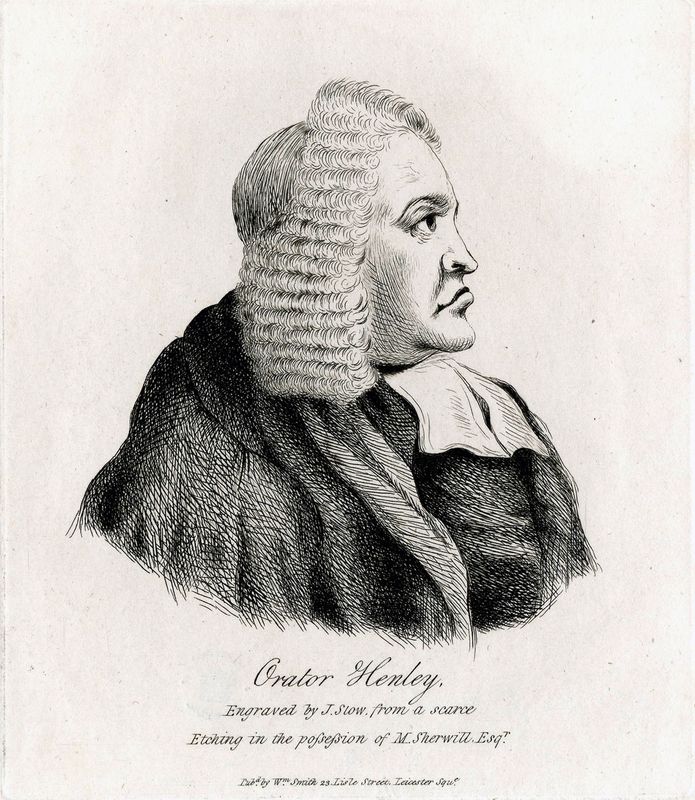

Graham Midgley’s The Life of Orator Henley was a revelation. I’d come across the figure of Orator Henley before, he was one of the big targets of The Dunciad, a running joke in The Grub Street Journal and one of the inspirations behind Christopher Smart’s drag review The Old Woman’s Oratory. What this book does is establish John Henley as more than a joke and even makes a case for him as a fascinating individual with some interesting ideas.

Born in Melton Mowbray, home of the pork pie, Henley was the son of a popular clergyman. He has a succesful school career at Oakham school before going to university in Cambridge. There his individuality and forward-looking nature seemed to assert itself, describing Str John’s college as “where I had the stupidity to be educated.” He found the place narrow, dull, incurious and utterly unequipped to give him the skills he would need for being a good vicar. What’s more the selection process to take holy orders struck him as a scam.

He went back to Melton Mowbray where he reformed the local school. He banned rote learning and corporal punishment, encouraging the pupils to develop their own individual thoughts and modes of expression. Compared to Johnson’s own ‘rational’ plans for education at Edial, Henley actually questioned the core practices and subjects of schooling.

Feeling that Melton Mowbray was too small a stage, he moved to the capital with the hope of getting a nice, fat London living. He maintained himself with regular preaching and lecturing gigs at some churches, and by slaving for booksellers. He created a series of ‘plain and useful’ grammar books in a range of languages. It was a good idea, but he wrote them all himself and simply didn’t know the twenty-odd languages featured in the series, trying to crib his knowledge from other books. Ultimately, it was a good idea badly executed and it brought him his first detractors. (He also wrote an epic poem about the Biblical Queen Esther, which is pretty good by all accounts.)

Despite a good start, he failed to advance in the church. Partly because his patron pulled out of politics and partly because the Bishop of London made some promises to him he didn’t keep (and thus earned Henley’s lifelong enmity). Henley decided to set up his own church, The Oratory. it was initially set up above a meat market, which exposed him to jibes about his butcher audience from then on. He wanted to return to the practices of a more primitive, ‘pure’ church, free of the accumulated dross of centuries (and bishops). He also wanted his Oratory to be more than a place of worship, but also a place of learning and set up lessons, lectures and educational pamphlets.

This was when the attacks really started. Henley wore his clerical garb at all times, even when he got drunk down the pub. He preached in a dramatic manner, a style which he felt grabbed his audience and communicated his messages better but many felt was over-theatrical. He also believed that all subjects could be interpreted religiously and held the potential for good lessons. As a result, he’d preach about political scandals, fashions and other seemingly frivolous things. He also believed that humour and satire were important tools in a preacher’s arsenal and the site of a man in cloak and bands cracking satirical jokes from the pulpit was too much for many. From his point of view, his peaching held, “universality of scope, liveliness of elocution and the various instruments of laughter” but to others he was a ranting weirdo. His fondness for puns didn’t help.

Most shockingly, his Oratory took money at the door to attend. While other churches lived off tithes, taxes, collections and even the renting of pews, pay-to-entry was far too close to theatre to his detractors. It was also possible to buy season tickets, with medallions of gold, silver and Bath-metal providing different privileges. He later tried to float The Oratory as a business, trying to get shareholders. These methods to pay for The Oratory easily led to accusations that he was only in it for the money, and Henley was able to live in middle-class comfort. Of course, he heavily denied this, saying, “little is got by an oratory: it is no occasion for envy”. What’s more, he felt his congregants got a good bang for their buck, not only with his lively style but his commitment to several original sermons a week, when other clergy would re-use their sermons or even buy them off other people. Samuel Johnson wrote a number of sermons for his friend, John Taylor.

As time went on, the religious side of The Oratory diminished. His celebrations of ‘primitive eucharist’ reduced in numbers, and his popular Monday evening lectures, which consisted of satirical news round-ups became the main event. The educational element of The Oratory kept going, and he offered lessons to teach people to “think, distinguish, definite reason, demonstrate, to dispute, conclude self-evidently” &c. Like his grammar books, this seems like a great idea, a people’s university - but he tried to teach everything himself and it ultimately seems like one of those pointless online ‘universities’.

The Oratory ran for thirty years, so it must have served somebody. It seems that there was an initial rush as people checked out the novelty, including Voltaire and Pope. Then things dropped off a bit, with bursts of attendance when Henley’s name was on people’s lips.

To maintain The Oratory in people’s minds, Henley wrote adverts. These started as hyperactive but straightforward accounts of the topics he would cover but mutated over the years. The adverts started featuring odd little tics, like “hei-day”, “job and hiccup” and “oh, my poor spectacle case”. Instead of describing the topics, they would feature strange little phrases or tortured puns. It was easy to assume he’d gone mad but Henley admitted that he “had written advertisements as seemingly incoherent as possible.” To understand the advert, you’d have to go to The Oratory. It’s essentially magazine-based clickbait.

Henley even had a place to run these adverts, his own magazine The Hyp-Doctor which ran every Tuesday for eleven years. In it, Henley played the character of Dr Isaac Ratcliffe of Elbow Lane, a doctor who cured ‘hyp’, short for ‘hypochondria’ and perceived as a form of melancholy. Despite one bookseller saying Henley’s name on books was “sufficient to make them be thrown aside”, The Hyp Doctor was often talked about and lived a long life.

John Henley is known to the present day from the reports of his enemies, and he made many of those. One of the fiercest was Alexander Pope, who eviscerated him in The Dunciad. Even more damning were the notes in the Variorum edition which attacked Henley personally. Henley believed these notes were written by Richard Savage, who had a hatred of him after he preached a sermon against Savage’s acquittal for murder. From then on, Pope was a main target, and Henley was just as nasty, mocking his size, deformity and describing his new poems as ‘diarrhoea’.

Pope then set up The Grub Street Journal and left it in capable satirical hands. The newspaper attacked him for the majority of its run; parodying him, sending people to make notes on his sermons, and turning his incomprehensible adverts into poems. Like most of his attackers, The Grub Street Journal ended before Henley’s Oratory did.

The other big ‘war’ was against Christopher Smart, who parodied the name of Henley’s Oratory in his Mother Midnight drag shows. Henley, wishing to defend his brand, attacked Smart, especially for his female persona and rumoured visits to Molly Houses. One of his sermons was titled, ‘Pimlico Molly Midnight translated to Rump Castle’ - Pimlico being a gay cruising spot. Smart seemed to enjoy the bantering back and forth in his The Midwife magazine and on stage and presumably the publicity helped them both.

As fascinating as this book is about Henley’s professional life, there isn’t much about his personal. He had a wife, Mary, who mainly stayed in the background. This seems to be because Henley didn’t have a personal life. Even on his off time, he wandered pubs and coffee houses, seeking arguments. When he died, he had no-one to leave his effects to. He had no friends.

This lack of friends seems the key to Henley’s failure. Had he collaborated on some of his projects, they may have been more successful. He may be remembered as an educational innovator or pioneer of a new kind of church but because he did everything himself, he had no-one to cover for his defects or help carry his loads. It’s impressive The Oratory lasted for thirty years until his death, but his inability to work with others meant it died when he did and his only legacy was as the butt of a joke.

No comments:

Post a Comment